As a parent, you really try to keep your kids from a lot of painful encounters but they never listen to your advice, as far as you can tell, which seems to be futile no matter how hard you try, and then the next thing you hear is crying.

Maybe that’s a good thing, if from their experience they learn more than you knew.

There are several books that fall into that model. Had I read them before completing Quaker Dover, I might have overlooked some fresh insights. But now that my book’s out, I really appreciate what else I’m finding.

Donald R. Bryant’s History of the First Parish Church is one of them. The 160-page volume, first published in 1970 and enlarged in 2002, offers another side of my argument of the Quaker invasion in town, for one thing, while relating other parts of the early years with, well, perhaps more discretion. And, my, I do admire his resources and tenacity.

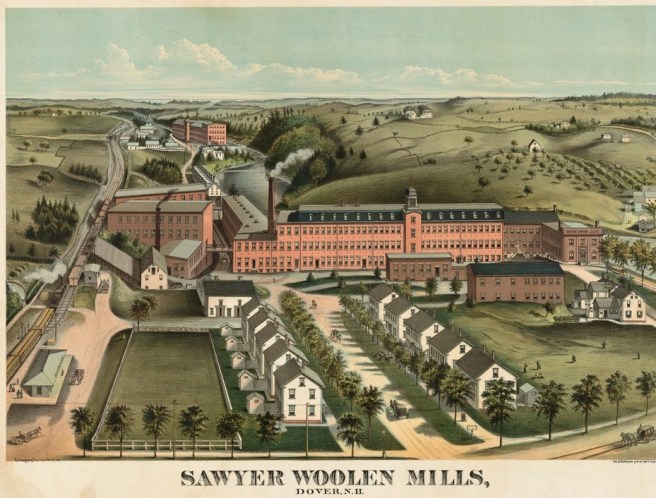

One of my favorite sections is the profile of John Williams that Bryant works into the narrative. Williams, a member of the parish, was, as he says “a visionary, a leader in bringing textile manufacturing to America,” and a cofounder of what became the big millworks in today’s downtown.

But he also became part of the faction of 26 male members who announced in 1828 they were leaving the church to join the Unitarian Society in establishing a new congregation. The split among the heirs of the Puritans into Unitarian or Trinitarian Congregational at the time paralleled a similar one among American Quakers into Orthodox and Hicksite. New England somehow remained Orthodox, as far as Friends went.

The plot within First Parish further thickens over the kind of minister it needed along with the construction of a new, and present, house of worship. What follows in the parish history is a turmoil that includes the changing economics of the town I haven’t yet found in the Quaker Meeting.

Bryant’s history then turns largely to the successive ministers rather than the congregation’s members and their influence in the community.

Still, I appreciate the comments by David Slater at the end of the book. He was First Parish pastor when I first came to Dover and quite engaging. He offered a checklist on how church life was changing that remains relevant, though nothing hit me more than this:

“Christianity is becoming more and more counter-cultural.”

That takes me back to the Quaker invasion into Dover, back in the mid-1600s.

As for the city’s other congregations? I’m anxious to hear more.