So some of the major hippie farm activity occurs right around or after Labor Day, much later than I would have thought. Whatever happened to Shayna, did she just fade from sight? Or was there some more decisive break? Here there is a big trip, must have been the 29th, after Lola was in the works. I came back from that trip seeing her as deep sorrow and resistance. Much Lola in this volume, and I’m surprised now to see she was barely 17, yet so well balanced. The volume also covers a week of vacation where I chose to stay at the farm, rather than go off to the ashram – notes, too, on looking seriously at poetry submissions. Much copying of Be Here Now rounds out the volume.

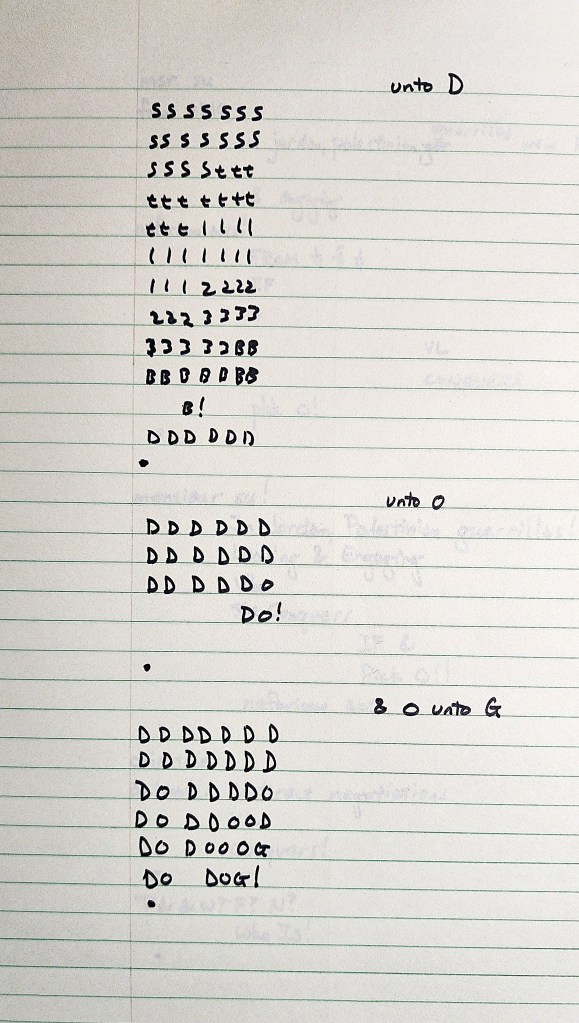

TO DANCE WITHOUT MOVING

~*~

Another volume that begins on a Saturday, 28:VIII:71

Aftermath Hurricane Debra

Trip to Rochester the next day.

Shayna’s sister was Tammy, not Serena as I had thought. “Beautiful … green eyes drinking in mine.”

Note that Lola and Shayna put their bras on backwards, as did Judith … as for Nikki?

At end of month, “much affinity for Aram Saroyan” … and Robert Creeley.

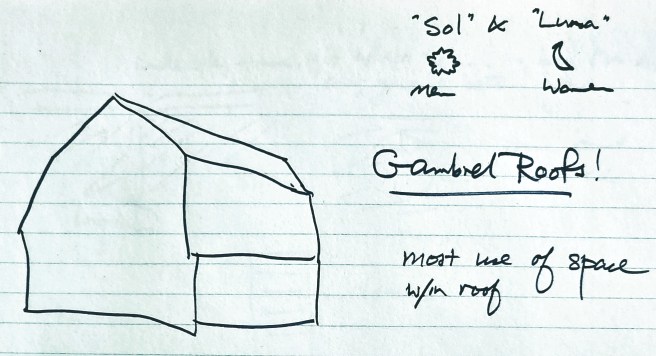

At campus bookstore, spent $16.55: far-out collection. Himalayan art, Neruda and Vallejo, two Rilke volumes, and 17th century English poetry survey. Passed on a $4 book of Blake’s art.

Decided to spend week of vacation at home. “Where else would I see more beautiful land?”

Got an amazing letter from my sister, seems the ashram trip together opened her up … read parts to Helene, “She sounds cute”

News from Cheri was essentially a nervous breakdown.

~*~

The commute to and from the office, down in the valley, from the rundown farm I shared in the highlands along the New York-Pennsylvania state line was memorable – a series of right turn, left turn connections of country roads. In the early mornings starting in August, the valley was often blanketed in fog below me.

~*~

Notes from Rochester trip: At Shayna’s parents’ house … books everywhere … Harvey’s Readers … Callas on the turntable … her mother was cooking what I dubbed Ira’s Stew, a pun on Iris … so now I wonder, who was Ira … I thought her brother, if one, was David … maybe that was Skye’s?

“Do you think you and Nikki will ever get back together?”

“No, not after Saturday’s phone call.”

Nikki was struck by my lack of my, using your, his, personal referents, calling it instead the car, the book, the dorm room: do I see the universe as mostly my stuff, or perhaps my stuff as the only real/valid stuff?

Wheel of torture [not fortune]

TO THE WOODS, WITH TYPEWRITER

Typing poetry, especially

Thank you Lola, I feel 17 …

In grocery with Rainbow (the nudist but this time clothed), and Pips’ mother standing in front of me.

I laughed, and she turned around. “Oh, hi! I knew it was you by your laughter. Nobody else laughs like you.”

Was I, uh, really, that weird?

My room as a universe I can comprehend.

On a later Friday, on way to Rochester [was I late shift next day?} … Shayna had found an apartment in Buffalo but with twists. Guys able to play cards there once a week …

Jack, Gwen, and Moe talking of moving out … Jack a source of leadership, initiative, and knowledge … Gwen a real down, everybody telling me she’s been giving off really bad vibes, confirming my impression …. If only she’d wash her dishes … while she doesn’t want anybody to hassle her, she hassles others, even by sitting to take a shit …

Rusty, talking: “When my father was released from the concentration camp in Poland”

Rusty to Speedo in kitchen: “We’d agreed that her being in Michigan was the best thing for both of us. I was losing identity of me, it was us. I said, sure, you can stay, I can’t kick you out, you know that.’

[Here, they stood in my eyes as a perfect couple.]

Rusty and Rainbow and me at the lake, one of the best days … hardly anyone around … warmish water, distant sun … his poison ivy so bad.

Another letter from Lola.

Ronco from Indiana visited, on his way to Ithaca, laughs like a little girl, gossips, yet good to see him. Slept with his clothes on using a mattress we dragged into my room. [We went up to Cornell the next day and I hitched home.]

Polly pissed to find about Willow; seems Mountain Girl [Willow?] wanted Polly to intercede to get Bob to pay for the abortion. “She’s really a fucked up girl.”

Molly’s pissed off about me and Gwen. “Boy, you should hear what she told me!” Also, a little later, “She was afraid she was pregnant.” Not me; we never got THAT far.

Walt upset ‘cause I left at 8 Saturday … 5½ hours. [Was I sick?] Tioga edition wasn’t there. A jam-up later. Also, I hadn’t finished editing a business story.

[Incinerated]

~*~

From Spiralbound Hippies, with commentary from now.