Tag: Inspiration

What is poetry, anyway?

After a couple dozen or so years that have been focused largely in the revision of fiction and then the roots of Dover Quaker Friends Meeting, itself a challenge to conventional New England history, I’ve found myself revisiting my trove of poetry.

It’s part of a big cleanup project that’s accompanying our downsizing move from New Hampshire to the far end of Maine, and I’m at a point of trying to discard everything I no longer need and put in order anything else I feel is of value.

As a result, several central full-length collections that had been presented piecemeal as chapbooks at my Thistle Finch editions blog are now released as ebooks at Smashwords.com and its affiliated digital bookstores. You’ll be hearing more about those as the year progresses.

In their place in the Thistle Finch lineup are new chapbooks of sets of my more recent poems, meaning ones from this century, though their origins go back further.

The task has come as a revelation, watching the evolution in my style and underlying voice. Each stage, reflecting geographical moves in my life and the upheavals of my closest relationships, edged me away from narrative-driven content to increasingly image and confetti centered clusters. Don’t ask me to explain them, they just are, whatever.

For me, poetry is a kind of mysticism – one foot in the inexplicable wondrous, the other in everyday life. Prose, of course, is more secular.

My newly released chapbook Aquarian Leap leads off the new run at Thistle Finch. Frankly, looking back over these, I’m not sure what to make of them other than the wild energy they inhabit. I certainly wouldn’t – or couldn’t – draft them today.

These poems, in some manner, still reflect the working of my multi-layered, mercurial thought process. (Never mind my heart, all the more elusive and often contradictory!) I love those lucid moments – sharp, brief – when everything, including thought and emotion, is centered, full, and stilled. Rarely, however, does my intellect flow in such a focused narrative. That requires more effort.

More typically, it flashes on something and then leaps to another, seemingly miles away. Some say this is characteristic of my natal sun sign. That is to say, the typical Aquarian will hear one subject and shuffle through fifty-two logical connections in a flash, and then blurt out something that will leave everyone else in the room wondering, “Just where did that come from?” (Except, perhaps, for another Aquarian, to whom it will seem perfectly logical.)

Often, my writing was constructed and amplified and then distilled from notes, many of them scratched out on a daily commute or on a hike in the woods, or sometimes even a twist while journaling. Curiously, when I assembled these into collage-poems, I was conscious of an underlying logic. That is, many snippets did not fit the emerging sense and must be laid aside. But a few others did, leading to what I hope is an internal thesis/antithesis/synthesis that’s ultimately beyond any surface or attempted cleverness. I prefer for my work to discover and uncover rather than invent.

The result in this set and a few ahead feels more like confetti. So there!

Something similar happens in disciplined meditation, such as traditional Quaker worship, where routine thoughts are patiently laid aside while one’s awareness clears and sinks to a more intuitive and integrated state. Perhaps some of that also infects these pieces.

I should confess to a few works by two poets, G.P. Scratz and Aram Saroyan, I’ve long admired, poems that defy explication or understanding yet spring from the intuitive burst that takes us beyond apparent meaning – and closer to a jewel-like condition.

Or even the freedom of dancing, which I find in a similar vein in the work of Philip Whalen, especially.

Consider the linguist’s Wolves and Consonants. (My reading of “Vowels” in a book title my elder daughter was reading.)

The growling of wolves adds a whole new way of following the Voice here.

As for any effort to define poetry itself? I guess I prefer the wilder side. Go figure.

You can find Aquarian Leap at Thistle Finch editions.

Kinisi 249

LIGHT

ON

WHITE

ALIGHT

On to the Pacific Northwest via the prairie and Ozarks

My second brace of fiction, ultimately three books in all, addressed the dozen years in the aftermath of the hippie outbreak, though I’ve tried to fudge the era precisely. I do think much of it is continuing.

Naturally, for me, they were semi-autobiographical, even though the protagonist is now a woman named Jaya who winds up with a much younger lover who becomes her husband.

The pivotal piece is Yoga Bootcamp, with her now as a central character, along with the guru they sometimes called Elvis or Big Pumpkin. My residency in the ashram was a transformative period in my life, even in the face of details I’ve since learned. We were a rogue outfit in the period when yoga took root in America. This down-to-earth story will probably scandalize your local yoga studio instructor, but the experience did reshape many of our lives, hopefully for the better. I’ve certainly carried many of its lessons far through some other faith traditions.

The central piece is now compressed into Nearly Canaan, originally an ambitious triptych that comprised the hefty novels Promise, Peel: As in Apple, and With St. Helens in the Mix. At the outset, a sense of place was central as Jaya relocated from a small town on the prairie in the American Midwest to the hardscrabble Ozarks to the apple orchard country in the desert of the Pacific Northwest, but the central theme now condenses as the question of how much influence one person can extend over others, hopefully for the better. I can ask now whether it would have been more compelling if she’d been conniving and manipulative.

The third book, The Secret Side of Jaya, is a set of three novellas, each one set in the places she lived after leaving the ashram. Each one, quite different, is premised on hearing and seeing figures in a locale that others don’t. Maybe you encounter them, too, where you are.

You can find these books in the digital platform of your choice at Smashwords, the Apple Store, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Scribd, Sony’s Kobo, and other fine ebook retailers. They’re also available in paper and Kindle at Amazon, or you can ask your local library to obtain them.

Kinisi 248

a cat, an iguana, and a white rabbit

saunter into a bar

No, I’m not going swimming nude in a group at a summer lake any more

As I’ve previously mentioned, for much of my adult life, I’ve thought of myself as a retired hippie. Or I’ve simply been called one by others. One of millions and, unlike many, one who’s not embarrassed to admit it, that was a time to remember, no matter how short we’ve fallen from its promise and potential, even though I’m not so sure how much I’d want to go skinny-dipping with others these days or even sleep on the ground or a mattress on the floor.

That said, I’ll also admit that much of my first year after graduation from college in the height of the hippie movement was deep misery and loneliness punctuated by playful discoveries. The writing of Richard Brautigan definitely fits in here.

What’s often overlooked in the era is that the central element was the hippie chick. Plus, personally, I was without one, since mine had moved on and left me stranded. (Oh, misery, oh, woe, I am sounding pathetic, but let’s move ahead.) My novel, Hippie Farm, celebrated her in her many guises, even if you can’t even use the term “chick” anymore without being corrected. At the time, though, it was a badge of honor and invitation – one leading, in this case, to that rundown farmhouse in the mountains outside a college town I definitely restructured in terms of fiction.

A second novel, Hippie Love, retold the same plot line from a different perspective, one more of a what-if optimism. I would love to have heard that story retold from their impressions. Ouch? Were they as lost as I was? One I’ve been in contact with all these years has shared her insights, helpfully, and another, reconnecting much later, barely remembered who I was. And here I had thought she might be The One. Oh, my.

In the light of the publication of What’s Left, those two books were then greatly revised and newly released as a single volume, Pit-a-Pat High Jinks. Compressing the two was a major effort, but ultimately satisfying, at least for me. So much happened personally within that short span.

The inspirations cover quite a cross-section of people, with one becoming a United Way executive, another a U.S. Attorney, yet another one an OBGYN physician. Not that you would have guessed it at the time. As for most of the rest, I have no clue. Some were real losers, likely lost to drugs now. Others, tragically damaged. Being hippie wasn’t always a quest for enlightenment, justice, and equality. And when it was, it was countered by powerfully invested self-interests. Sometimes I’m surprised any of us survived, even before we look at the Vietnam veterans on the other side and their continuing traumas. Not all addicts, by the way, were hippies.

Flash ahead, then, and I don’t see youths today finding community anywhere, much less a shared cause. This is supposed to be an improvement?

Contrary to many people who lived through the era, I saw much that happened needs to be remembered and often cherished, even comically. It’s a place where people can begin rebuilding. I’m holding on, then, in my Quaker Meeting as one root to be grafted.

Look closely at the women, especially, and see how much of the legacy continues in spite of everything. (The kids today have it right, their perception of hippie as a girl thing.) Or, as they say. We’ve come a long way, Baby.

Yet that hippie label, I should add, has undergone its own transformation, rarely positive. Alas. Especially for us males.

Most of them, I hope, come across better in the book.

Still, it’s an account of history as we encountered it.

You can find Pit-a-Pat High Jinks in the digital platform of your choice at Smashwords, the Apple Store, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Scribd, Sony’s Kobo, and other fine ebook retailers. It’s also available in paper and Kindle at Amazon, or you can ask your local library to obtain it.

Kinisi 247

I sing

on the cake

…

And God made female

cardinals, too

For better or for verse, here are more lodes I’ve also mined

By the standards of many, I’ve been a prolific poet, though if you consider that just one new poem a week would come to more than three thousand now.

Sounds about right, even with the arduous revisions they underwent, pressing the original inspiration into something quite different, always in an “experimental” rather than traditional vein. Add in all the hours of submitting the results to journals and small press openings, and all the rejection slips that followed, it was an obsessive amount of time – I had been warned that even “successful” poets averaged 20 rejections for every published poem. And beyond that, simply preparing a “clean” page for those submissions back in the days of typewriters pressed the limits of patience.

Still, poetry could be done in shorter spurts than fiction in my free days and nights while I was engaged working fulltime in a newsroom. As a minus, it did divert my attention from the local news scene and related gossip, but it did sharpen my editing and writing skills, both of which chafed at the limitations of newspaper style.

Many of my early poems sprang from my journals, something that changed over the years, especially as I got into Deep Image and related techniques. While more than a thousand of my poems were published in journals around the globe, book-length collections remained elusive. Now, however, some are available as ebooks, allowing you a chance to sample my evolution over six decades.

Here’s a lineup:

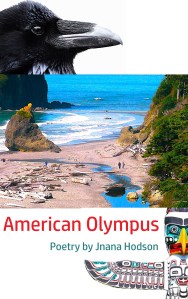

American Olympus: This longpoem is also a mythopoem set in a single week of camping on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington state. The book came close to being published by a prestigious letterpress imprint but fate intervened, sending me spiraling back eastward. Many other nature and landscape poems reflecting my experiences from one end of the continent to the other and back in my early adult years await full collection. Please stay tuned for future appearances of those works.

Braided Double-Cross: Intense attraction, sexual ecstasy, and long-term dreams ignite this set of contemporary American love sonnets that reflect the conflicting emotions and unspoken expectations that surface in the eruption of breakdown and breakup. The set, my first run of poems composed as a series, explores passions that sugarcoat realities and betrayals. Sometimes something so truly hot leaves a lover branded for life.

Blue Rock: Continuing in the conflicted passions line, these poems reflect attraction, romance, and the aftermath in today’s society. Just groove to their beat.

Trumpet of the Coming Storm: Admittedly polemic, these are brimming with buried anger erupting at last. Sometimes you just can’t ignore politics, even in a historical perspective.

Hamlet, a Village of Gargoyles: This playful investigation of human identities alternates between gossipy and confessional, set within the context of close community. The collection now hits me as somehow prescient, considering that I’m now living in a real village with characters I hadn’t considered. The tone is contemporary with nods to Shakespeare and Chaucer.

Ebook formatting does limit the visual array of what you would otherwise find on a defined page of paper, but it does make my daring work available inexpensively around the world. I can live with that and so can you, especially if you’re reading on a smart phone.

I promise, there will be more.

You can find these in the digital platform of your choice at Smashwords, the Apple Store, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Scribd, Sony’s Kobo, and other fine ebook retailers. Or you can ask your local library to obtain them.

Kinisi 246

night

note

knot

On my own, I was writing contemporary literature, except that it turned into underground history

When I was starting out in my career and sitting at the edge of the semi-circular copy desk, one broad story I kept seeing in the headlines didn’t reflect what I was finding in daily life. It was the hippie experience, told one the public side as drug busts, antiwar protests, and rock concerts, while the personal side I sensed something much broader and transformative, which was largely ignored.

Tom Wolfe, who had come to prominence as a newspaper columnist, was right in saying that the great hippie-era novel needed to be written, though he was wrong in thinking a single book could cover it.

From my perspective, a traditional facts-and-quotes approach couldn’t touch the emotional reality, pro or con. Interviewing celebrities posing as leaders wouldn’t work, either – they largely betrayed us, maybe like never-a-hippie Trump would do later. Hippie was a grassroots movement on many fronts, many of them outside of the big media headquarters in the biggest cities.

In previous Red Barn posts, I’ve touched on many of the hippie movement’s continuing influences, things our kids and grandkids take for granted, but so much – especially of the broadest nature – remains to be examined and presented. I’ll leave that to someone else who can give it full and fresh attention.

For my part, I leave four novels as foundations for others to build on.

I’ve looked hard for work by others but found little yet faithfully left reviews online where I’ve could. Those works are, alas, slowly vanishing. Yes, we are passing.

I am haunted by a definitely hippie copy editor from the year I interned as what we called the rim, but he was gone when I returned a year later, perhaps after pressing for union organization. A lot had changed in those nine months. I wish I knew more about him, other than the ticket for Woodstock that I couldn’t accept, considering the scheduling and my bicycle as my only transportation.

~*~

The core of my perceptions remains in four novels to my credit.

Daffodil Uprising: I was on campus when the repressive constraints of institutional America blew apart in the late 1960s. Crucially, many of the radical currents emerging on both coasts began connecting in academic nerve centers in the Midwest – places like Daffodil, Indiana, where furious confrontations exposed positions that later generations now take for granted. My novel revisits the upheaval and challenge, both personal and public, triumphant and tragic. As I still humbly proclaim.

Pit-a-Pat High Jinks: The hippie movement that is usually thought of as the Sixties actually appeared most fully during the Nixon administration, 1969-74, and brought changes that younger generations now take for granted. Yes, the ‘70s. In my case, that was Upstate New York where I lived in bohemian circles near the downtown and then on a rundown farm out in the hills where a grubby assembly split the rent and a bit more. My, we were so green and so wild-eyed.

Subway Visions: There were good reasons so many of my freaky housemates and new friends came from the Big Apple. My jaunts to The City, as they called it, provided high-voltage flashes of inspiration that ranged from grubby to psychedelic. It was a whole new world to me, even as a frequent visitor.

What’s Left: So much remained unvoiced and unexamined in the aftermath. I drafted a series of essays that came together as a creative non-fiction volume, but that went nowhere. But then I had the flash to reshape it from the encounters of the hippie protagonist of the previous three books but explored by his curious and snarky daughter. My intention for a big book about the revolution of peace and love turned into one asking what is family, primarily. Hers was quite the colorful circus.

~*~

I still believe there’s much in these that’s “still news” despite the dated surfaces that usually pass for the era.

This year, though, I’m finally saying good-bye to maintaining an effort to engage in an awareness. It’s ultimately in others’ hands.

You can find my novels in the digital platform of your choice at Smashwords, the Apple Store, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Scribd, Sony’s Kobo, and other fine ebook retailers. They’re also available in paper and Kindle at Amazon, or you can ask your local library to obtain them.