Journalist? Perhaps a very special secretary, in the old aristocratic sense of personal aide, except on behalf of the people …

You never know what we'll churn up in cleaning a stall

Journalist? Perhaps a very special secretary, in the old aristocratic sense of personal aide, except on behalf of the people …

Here we are, Thanksgiving Day, and I’m finally getting around to my reactions to Nathaniel Philbrick’s 2006 hit, Mayflower: Voyage, community, war.

Admittedly, having examined some of the period he covers, from the origin of the faithful and their sailing in 1620 through their struggles up to 1677, but from the settlements north of Boston, I come at the book from a different perspective than most readers. I appreciate his efforts to present the Separatists – the term he settles on rather than “Pilgrims” – as distinct from the Puritans who would invade New England a few years later. I also appreciate his emphasis on the non-members of the faith who participated in the Plymouth Colony settlement as well as the heavy financial burden the enterprise carried, which are details I develop more briefly in my own volume, Quaking Dover: How a counterculture took root and flourished in colonial New Hampshire.

What struck me in my reading was how little awareness Philbrick conveyed regarding the activities not just on the Piscataqua watershed, the center of my book, but north of Boston in general, including Salem, especially in the years before the Puritan influx. Sir Ferdinando Gorges, whom I see as the godfather of New England, is not even mentioned, though he and his investors were active behind the scenes in England. The Piscataqua venture was a source of food for the desperate Plymouth settlement and provided twice as much funding for anti-piracy efforts, among other things.

Philbrick, not surprisingly, takes a conventional gloss on Thomas Morton and the Merrymount settlement without noting that its roots were in Devonshire folkways, not just in personal eccentricities. Dismissing him as “a jolly down-on-his-luck lawyer from London” overlooks the argument that the settlement was thriving and apparently more successful, economically and as an attraction, than Plymouth.

Philbrick’s examination of the attempted Wessagussett settlement as a Plymouth satellite clarified some of the events for me, since it falls between Plymouth and Dover as the oldest permanent settlements in New England. I am also glad that he included the struggles and near devastation of the Jamestown settlement for perspective. The Virginia colony, like the Mayflower, tends to be romanticized in the public eye. The gritty realities need to be spotlighted, too.

He acknowledges the second ship to the Plymouth settlement, the Fortune, in the fall of 1621, which doubled the population of the colony as well as its growing pains. The next ships, the Anne and Little James, arrived in the summer of 1623, but only one is named, briefly. I follow their impact through immigrant William Hilton, the brother of the founder of Dover, New Hampshire, and a Fortune passenger. His wife and children came on the Anne. Though he’s often erroneously identified as co-founder, he didn’t arrive north until he was ejected from Plymouth after he and his wife had a child baptized by the Anglican John Lyford, an event that triggered events that Philbrick briefly notes. I am now wondering if Lyford later, in 1628, performed the first Anglican wedding in New England, the one uniting Samuel Maverick and the widow Amias Cole Thomson on an island in Boston Harbor. That, too, weaves back to my book.

Within the period covered in Mayflower, Quakers were making inroads into the Plymouth colony, though Philbrick makes only fleeting reference to the persecutions led by the Puritans.

While he goes into great detail regarding the Pequot War and the one after, known as King Philip’s, he makes no mention of the mock war games in Dover in 1676 that sent an estimated 400 or more Natives into captivity and is often credited as bringing the King Philip’s conflict to an end. Some were hanged but many, women and children, especially, were sold into slavery and exported.

Still, he develops a much more complex understanding of conflicts among the varied tribes and their leaders than is usually seen. The concept of a unified “Indian” front quickly crumbles away.

I’m also interested in the Winslow lines that left Plymouth, including those who came to the Piscataqua region about the time William Hilton did and others who joined with Dover Friends in establishing a Quaker presence in what eventually became Greater Portland, Maine.

For southern New England, the closure of King Philip’s War, where Philbrick’s book ends, essentially ended the conflicts with the First Peoples. Not so in the north, where fresh outbreaks would hammer on for decades, abetted by the forces of New France, ending only with the Treaty of Paris in 1763.

After four decades as a daily newspaper editor, I was recognizing I was among the last in a long tradition. I do worry about the future of community and democracy in the aftermath.

As I pitched my novel at the time, “Hi, my name is Jnana Hodson and I’m not surprised American newspapers are in crisis. In my four decades as a professional journalist, I’ve seen news coverage under attack – not just from the outside, but more crucially from owners who first bled billions from its renewed growth and vitality and now give the product away without a viable business model in sight. My novel, Hometown News, pays homage to the battle and what could have been, along with journalists’ role in the survival of communities across the continent and democracy itself. Along the way, Brautigan and Molly Ivins meet Dilbert and Kafka on the prairie, even when their names, sex, and races are changed. May I introduce you to the full story?”

An alternative version went, “Hi, my name is Jnana Hodson and my career as a journalist has placed me in enough decaying industrial cities to shape my novel of high-level global investor intrigue. If you think Dilbert tells of modern business operations, think again. May I show you my take?”

A bigger question was why anyone would be interested in this or see themselves impacted by these corporate machinations.

At their best, daily newspapers have shaped both a central identity for localities across America, and their conscience.

For many years, despite the arcane business structure in which advertising rather than sales of copies provided the bulk of the income, hometown newspapers were cash cows for their owners – who, in turn, paid their reporters and editors minimal wages.

The resulting management practices – reflecting those of surrounding corporate retailers and manufacturers – have put news coverage at risk, endangering both the communities and democracy itself. How will they, like the reporters and editors, survive?

As a journalist, my touchstones have been Accurate, Informative, Useful, and Entertaining. I wonder how those apply to poetry, as well.

The novel is cast on an experimental frame, one that anticipated AI and then backed away from it. The daily events, however, get weirder and weirder as the demands and tensions ratch up. You might even think of it a dystopian.

That said, you can find Hometown News in the digital platform of your choice at Smashwords, the Apple Store, Barnes & Noble’s Nook, Scribd, Sony’s Kobo, and other fine ebook retailers. It’s also available in paper and Kindle at Amazon, or you can ask your local library to obtain it.

One of the joys of blogging has been the way it’s opened connections I wouldn’t have otherwise found.

An example of that came after an email exchange with Paul Glover, who had come across my references to Hub Meeker, who had been the fine arts columnist at my hometown newspaper, the morning one that later gave me an internship as my first professional stint.

Hub had a position that was long my dream job, but a rarity in American journalism. Fine arts coverage is marginal, at best, and these days often limited to press releases rather than performance reviews. Even the Washington Post is a near zero on that front.

And there I was in the same newsroom, sometimes even going to lunch or dinner with him.

You can imagine.

Shortly before my graduation from college, Hub moved on from Dayton and eventually from sight altogether. And his position went to another, more established figure, rather than me, despite my own little fan club in the room. At this point, I’m thinking it would have turned out disastrously.

(I need some time for that thought to sink in.)

~*~

Turns out Paul knew Hub from a different perspective, a stepson of sorts, though falling in that range of family relationships that currently lack an exact word that fits.

He related that Hub had recently died and was wondering if I had any memories

or stories of interest that I could send his way in British Columbia.

So here’s my quick stab.

~*~

Naturally, you’ve stirred up so much more.

For starters, I’m not sure what high school he attended or even college. Ohio University? As for a major? Or even how he got hired at the Journal Herald, though Glenn Thompson had an eye for the unusual. Glenn hired me because of a letter to the editor I had submitted and then talked me into changing my major at Indiana University, from journalism to political science.

I graduated from Belmont in ’66 and gather that you’re a decade or so younger. Do fill me in.

The art institute, as you probably know, was undergoing a major shift at the time, from a collection that had included samurai armor and an Egyptian mummy in its displays to instead focus on picking up first-class works in a particular style or period rather than second-rate works by big names. Hub was happy to proclaim the purchase of pre-Columbian pieces at a time when nobody else was aware of their glories.

The DAI was also on the cutting edge of the arts scene, including its degree-producing art school, which several of my friends attended. Or, as my high school art teacher once said during a visit to her home when I was home from college with my girlfriend (from the other side of town), it was the kind of place that displayed the constructions of my girlfriend’s mother and her close friend slash mentor. Don’t know if she called it rubbish, but she certainly didn’t see it as “painting.”

By the time of Kent State, Dayton was already in a downward economic cycle — National Cash Register had laid off almost all of its workforce and was demolishing its factories, and General Motors’ five divisions were all getting hammered, too. The dysfunctional school board’s refusal to work on racial imbalances led to court decisions that, well, pretty much destroyed public education in town.

You were lucky to escape.

You touch on your parents’ marital difficulties. From meeting Hub’s wife a few times, I got the feeling that their relationship was rocky. Yes, she was British and daffy and likely neurotic — a smoker? — all with their charms, and, yes, quite pretty (brunette?) to my 20-year-old eyes. I later wondered how much of that factored in the decision to move to Rhode Island. Looking back, I do believe she really was hitting on me late one afternoon, though I rather brushed it off at the time. (Gee, I was still virgin. Hard to admit that, even now.) (Ditto, for another encounter, at school a few months earlier.)

I’m also wondered how Hub managed financially after leaving Dayton. Writing is rarely lucrative, even for some major authors, as I’ve learned from one friend who envied my steady income while I envied his New York Times critical acclaim. Well, Paul, you know the arts scene. Did you continue in that vein or find another path?

Being together 50 years, though, is quite an achievement. I always saw Hub as a gentle soul. I hope he was that in your relationship, too. Stepping in as the new male authority figure is rarely smooth, as I found in my own remarriage.

I am impressed by your efforts on the memorial service and hope it brings comfort to your mother, you, and the rest of those closest to you.

Oh, yes, and thank you for visiting the Red Barn. I was surprised to see I had mentioned Hub five times over the past dozen years.

~*~

This must have been in a follow-up dispatch:

Hub had what for me was a dream job on a newspaper. His wasn’t just a column – ideal enough – but one covering the fine arts, all of them – visual, literary, and performing – just as they were becoming important in my own adolescent life.

At the time, Dayton was a thriving industrial hub that also had a heavy Air Force presence. It wasn’t someplace you thought of as having an artsy side, even as the ‘60s took shape.

Glenn Thompson, editor-in-chief of the morning newspaper, one of a moderate Republican stance, believed in raising readers’ visions a bit higher. Somehow, in recognizing Hub’s potential, he created the State of the Arts beat.

For Hub, this was an opportunity to discover creative work in many veins, and in doing so, he nurtured a growing scene. Vanguard Concerts surfaced to bring top-notch chamber music to town; an opera company was formed, presenting some up-and-coming stars along the way; his coverage of new architecture was cited by, I believe, it was Time magazine. The local art museum was hailed by the New York Times as, “Dayton, Dayton, rah-rah-rah,” no doubt influenced by Hub’s columns.

He did get to cover the arts elsewhere, too. Some of his columns reveled in the richness of London, which had all of five symphony orchestras.

Turning to Cincinnati, with its zoo, he opened a report with “Hip, hop, hippopotamus, it’s the zoo. Where …” and then took us behind the scenes with a world we’d otherwise never see. The story was accompanied by a page-wide photo of a giraffe’s neck stretched out to an ice cream cone.

Every fall he and the outdoors writer headed off to the hilly part of Ohio to review the fall foliage. Their columns then ran side-by-side. Fun stuff, seeing the same event from different perspectives.

And then, in my sophomore year of college, I got to intern at the Journal Herald and actually meet the guy, go out to lunch – I remember the open-face cheeseburgers from one of those at an old-fashioned downtown dive, even share a staff party or two.

He admitted feeling he was on thin ice, trying to cover so much. I think the spirit of wonder and curiosity he conveyed made up for any lack of formal expertise. He did come from humble roots on the wrong side of the river, as I recall – well, my part of town wasn’t exactly classy, either. And then there were rumors of a used hearse Hub and his wife drove, perhaps somewhat scandalously.

And then, shortly after I transferred to Indiana University, the paper announced that Hub was off to Rhode Island.

It hit me as a shock. He had been a crucial influence shaping my own artistic tastes and outlook.

~*~

What I learned in return was that Hub had left journalism but done some writing along the way. Spent his later years in Canada and serving in community service of various strands. In the photo that was enclosed, both he and his longtime sweetheart look very happy.

Through much of my career, I never quite appreciated the sports staff. The sports desk was over there in its own corner or maybe even a separate room or suite. Unlike the cops beat or business or education or even the courts coverage that filled the “real” news.

But it did produce some of the best political writers and editors in the business.

Their perspective, facing two teams, essentially – especially baseball, with its daily games in season, and delivering on tight deadlines – provided a character-based focus in contrast to those of us who were more policy driven.

Its baseball angle for some fine writers first came to my attention in John Updike’s prose and later David Halberstam, though they didn’t have newspaper experience.

The drama of contests, strategies, determination, hard work, fairness, and a vision is central in their work, along with the reality that so much of the field is about losers who persist and sometimes come out on top or have lasting influence, especially within the realm of a hometown team. Not a bad paradigm.

These former sportswriters and editors were around me throughout my career, though I never kept a list and now wish I had. On the national scene in my time, though, I can point to Charles P. Pierce, Mike Lupica, Ward Just, and Mike McAlery as prime examples of those who broadened their game.

Curiously, I haven’t seen that crossover occurring much from a football foundation. Perhaps that game’s more like a weekly television series or shouting match than the realities of a daily grind.

I’ll let up for now before I’m playing out of my league. But I do want to hear more from others – players and fans alike.

I’m still reeling from the decision at the New York Times to disband its sports department.

Admittedly, for much of my career, a newspaper’s sports staff was a mystery, set aside in a different room or even more elaborately from the rest of the reporters and editors. Sports seemed to demand a disproportional amount of newsprint, too, compared to, say, world news or even politics.

Only later, working at the fringe of Greater Boston with its intense team fanaticism, did I come to see things differently.

For one thing, the Boston Globe had some great sports coverage and I soon admired some of the writers. For another, I could see how the Red Sox, Patriots, Celtics, and Bruins held the region together at a gut level as an extended community. Many of our obituaries, for instance, included the line, “She was an avid Sox fan” or the like. Devoted? Sometimes “rabid” would have been more accurate, but “avid” was the term of choice.

As a journalist, I envied the excellence at the top papers that resulted from deep planning and commitment as well as top talent. I could see that a few papers stood head and shoulders above the rest on that front – the Globe, Washington Post, Chicago Tribune, Los Angeles Times, and, of course, the New York Times. Gee, they even had expense accounts and travel.

~*~

Thus, the idea of shuttering a first-class operation seems extremely drastic.

Yet, the Times does differ from most other dailies. It is, for one thing, a national newspaper far more than a New York paper. High school sports are trivial in its scope, as are many college games. The city itself has not just one or two professional teams – or even four, like Boston – but two in baseball alone and two in football plus two in basketball, does anyone even care about hockey or soccer or tennis or golf or whatever else in that crush? There’s only so much space in a paper, after all.

Much of the coverage will be drawn from the Times’ subsidiary website, The Athlete, which already has a national focus and staffing. There is reason for concern, though, that those positions do not have union representation, unlike the Times.

The decision likely reflects a recognition of major shifts in sports coverage across the city and the county as well. Internet access means that scores and other statistics can be instantly browsed from anywhere, rather than having to wait for the paper to arrive.

Cable has expanded game availability to fans, even those living far from the teams.

And then what’s there left to say after ‘round-the-clock sports talk radio and all the call-in chatter?

The Times’ arts coverage has already undergone a similar evolution, with less coverage of events and more emphasis on trends and influences. That seems to be what we can expect on the athletic front next.

In the newsroom, we were always perplexed that a section that generated so much readership – presumably male – failed to garner much advertising support. Department stores and supermarkets didn’t want to appear there, nor did auto dealers and parts stores. As for restaurants or movie theaters or politicians? Remember, advertising, rather than subscribers or newsstand sales, paid the bulk of the bills.

Deadlines, too, often hinged on the final score of the day, at least for the morning papers. Back in the day when we still had afternoon papers, you could get a more leisurely account there before the next game. Either way, those deadlines have moved up for other reasons. No waiting around breathlessly.

~*~

How this will play out on local papers remains to be seen. All I know is that staffing and space and advertising are all way down there, too.

I‘m feeling defeated. Both the New York Times and the Washington Post, as I’m seeing, have capitulated. As a copy editor who spent a career trying to preserve the language from utter erosion, this hurts.

Quite simply, it was two words, not one.

Oh, the enormity here! Where do we draw the line anymore? Or is that any more?

As a newspaper editor, I was often startled in looking at coverage from the other side when something I was affiliated with was subject to a story. Or even more startling, when I was quoted and seeing how it looked it print.

It was like working in a restaurant kitchen and shipping dishes to the dining room and then, on a night off, going in for a celebratory dinner.

Seeing a report through the readers’ viewpoint really could be eye-opening. It’s not the “names-is-news” philosophy that many small-minded editors and publishers pursued, either. That approach could be even more boring than reading the phone book. Remember those?

The backbone of most of American newspapers has been the way they connect with their local communities. As one wise editor once told me, it should be news of local interest, rather than just happenings in the place itself. I spent much of my career trying to open parochial outlooks to an awareness of the wider world, both directions, and I do believe that can happen and even be exciting.

When I was calling on daily newspaper editors across the Northeast as a syndicate features field representative, I was surprised by how few of the papers gave a taste of a unique nature of each of the communities. Many of the editors thought of local news as city council and school board meetings plus high school sports scores. As I argue in my novel Hometown News, the real stories – the kind that come home – are found elsewhere and require more reportorial digging. That’s one reason I’ve long advocated local columnists (real writers, not dilettantes, though skilled amateurs are welcome). Few papers had even that much.

When former U.S. House Speaker Tip O’Neill famously proclaimed “All politics is local,” he understood those roots.

~*~

A decade after I’ve left the newsroom, I’m directly experiencing that again, or more accurately, its lack.

In the past 20 years, the number of people employed in newsrooms at American papers has dropped about 60 percent. That leaves far fewer people to write about what’s happening or even be aware of what’s going on at the grassroots level where they live. Much of the nuts-and-bolts editing is being done in clusters far from the paper itself, removing another layer of local nuance and understanding.

In my case, in my participation in events celebrating the 400th anniversary of the founding of Dover, I’m seeing the local paper is doing far less coverage than I would have expected. Not after the family that owned it for generations finally sold out to a media conglomerate.

That disconnect isn’t just print media, either. New Hampshire Public Radio no longer originates any content in the Granite State, as far as I can see. Two decades ago, appearing on one of its shows would have been a natural for a local author like me.

Quite simply, it’s disappointing and a bit scary.

Here we were, designing the newspaper of tomorrow. Meaning the next day’s editions.

As for the newspaper of the future?

Never thought it would be built around the dimensions of a computer screen or even a smart phone or have all of those links to follow.

The changing economics and business model are another subject altogether.

How are you getting your news?

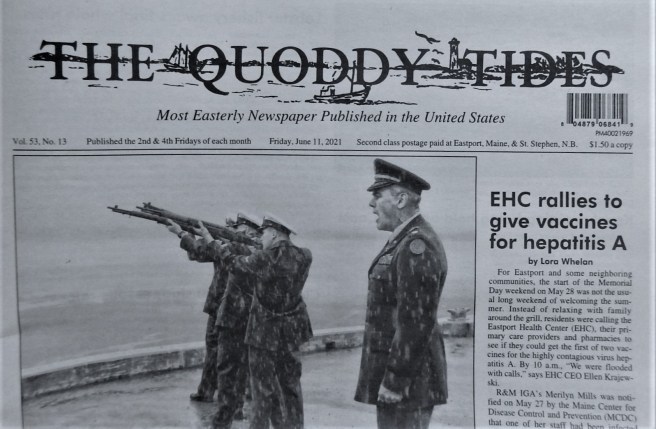

One of the factors in our decision to relocate to Eastport was the quality of the local newspaper, which appears every second and fourth Friday of the month.

There’s nothing flashy about its tabloid-format editions, but everything I see strikes me as solid, even compelling, community journalism.

The quirky – and unique – use of Tides rather than Times in its name is not just humorous but altogether appropriate. The paper reports on all of the communities the tides touch on in Washington County, Maine, as well as many in neighboring Charlotte County, New Brunswick.

One of my ongoing criticisms of American newspapers over the past half-century is that very few of them give you a feel for the place they serve. Ownership by out-of-state corporations is only part of the problem. Continuing cutbacks in coverage is another. (I play with those and other factors in my novel Hometown News.)

For most dailies and weeklies, there’s a generic look and taste in the stories. Everybody has city-council and school-board meetings, for heaven’s sake, and most car crashes are just as boring.

Somehow, though, that’s not the case with the Quoddy Tides.

Consider the lead on a report of the start of the important commercial scallop harvest, a story that was presented on Page 2 but teased from the front page by a dramatic black-and-white photo of a fishing boat plowing through rough seas:

“Winds gusting over 50 knots did not deter many Cobscook Bay area scallop fishermen from going out on the first day of the season on December 1. About three-quarters of the fleet of over 20 draggers based in Eastport and about 10 boats from Lubec headed out that day.”

Remember, it’s not just windy with choppy surf. This is December, blowing icy water. As for a feel of the place, just listen to the quotes in the next sentence:

“Lubec fisherman Milton Chute observes, ‘The tops were blowing off the water like it was pouring,’ and Earl Small of Eastport says that while it was ‘sloppy steaming back and forth,’ once the boats were on the lee shore either off Lubec or down in South Bay, it wasn’t bad towing out of the wind. ‘It’s not as dangerous as people think,’ says another Eastport fisherman, Butch Harris, noting that two or three boats will fish together in case anyone gets in trouble. ‘It was a rough ride out, but once you’re there fishing it’s not that bad.’ Harris points out that scallop fishermen have only so many days that they’re allowed to fish. ‘If you don’t go, you lose it,’ he notes.”

Much of their quotes, I’ll venture, is pure poetry. And off the cuff, at that.

The rest of the story fills out the page, detail after detail. I bet you’ll think of some of this dedicated labor, too, next time you eat seafood.

The Tides was founded in 1968 by Winifred B. French, the wife of Dr. Rowland Barnes French, M.D., and mother of five. They moved to Maine from Arizona in 1953 so he could help found the Eastport Health Center, itself a remarkable story in community medicine.

Winifred had no background in journalism, but she saw a need, studied hard, and ventured forth in launching and editing a small-town paper with a regional outlook. In 1979, for good reason, she was named Maine Journalist of the Year. Remember, the Tides isn’t a daily or even weekly newspaper, it’s every two or sometimes three weeks.

Reporters attend public meetings rather than chasing afterward by phone, correspondents provide meat-and-potatoes servings of neighborhood interest, Don Dunbar contributes top-drawer photography, and local columnists all weigh in for what becomes must-read pages throughout the area. The mix skirts the glib boosterism and doom-and-gloom morbidity too prevalent elsewhere.

Winifred died in 1995, but son Edward French and his wife, Lora Whelan, continue on her model. (Another son, Hugh, heads the Tides Institute and Museum – note that Winifred’s sense of “tides” continues there, too.)

I like the fact that the stories don’t carry datelines. Nope, the reader doesn’t get a chance to turn off on the basis of a single word. The region is closely interlinked by people living in one place and working in another or having family elsewhere, so it’s all of interest or should be – both sides of the U.S.-Canadian border.

I also like the fact that headlines come in just two sizes, with a serif face used for a touch of variety. There’s no need to scream to draw attention. Instead, we get an orderly and fair-minded sensibility.

So that’s an introduction. I could go on and on.

In some ways, it reminds me of Annie Proulx’ novel The Shipping News, without the dreariness and grimness.

One thing I would tweak is the nameplate, which goes back to the first edition. That shoreline still seems to strike out the paper’s name.

Still, it’s a joy to be retired and not have to be in the midst of producing all this. These days I do delight in being able to sit back and simply enjoy what I’m reading – even if I do on occasion feel an urge to “fix” something on the page.

What – or whom – do you look forward to reading the most? On a regular basis. (Apart from this humble scribe.)