As you’ve probably noticed in other posts here this year, I’ve been trying to recall some of the authors and books having an influence on the earliest drafts and later revisions of my novels. As I’m writing this, most of my personal library is still in storage – or other volumes, purged long ago to make room on my shelves for more – and my journals under wraps during the house renovations. I’m having to rely on memory, faulty though it may be.

Look, I don’t want these posts to be about some poor neglected novelist blah-blah-blah, but rather as one account of surviving in a writer’s life, maybe as a bit of advice or even encouragement for the next generation or two.

That said, I can state that my subway project sprang from Richard Brautigan’s Trout Fishing in America as its model. Think short, playful, imaginative with an image slash idea as its central character, like a children’s story for Woodstock reaching young adulthood. William R. Burroughs’ Naked Lunch also cast a spell as a free-floating state of mind.

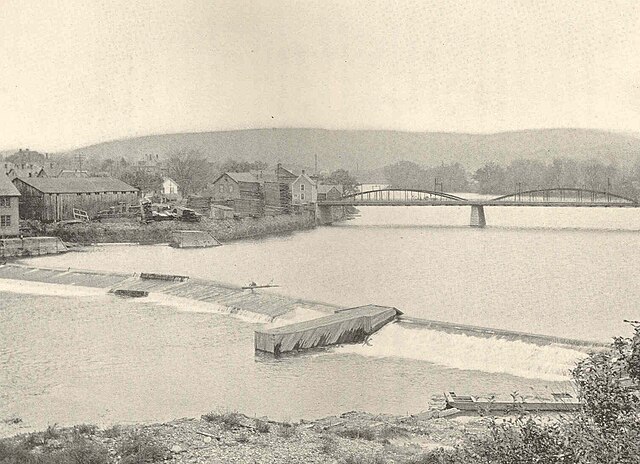

For me, hitchhiking in subway tunnels was a fantasy symbolizing the hippie experience as I encountered it during my time living in upstate New York. You know, underground with urban roots yet flourishing out in the countryside where you could stick out your thumb and go about anywhere. Yes, though I didn’t fully comprehend it then, that Woodstock crowd was mostly from New York City and its suburbs.

The symbol even implied a degree of freeloading rather than responsibility.

While awaiting publication, the manuscript kept growing from its 1973 first draft, typed while sitting cross-legged at my beloved Olivetti 32 typewriter, through a revision shortly after that and probably another in 1976 before I packed up for the Pacific Northwest, where yet more would be added to the text with quite a backstory in addition to a superstructure out in the foothills somewhere north of Gotham.

This was well beyond the initial Brautigan flash. What I had was, in fact, unwieldy, and nodding toward Brautigan’s other fiction and a lot more. Unlike me, he kept most of his volumes short.

And then, somewhere before reaching my sabbatical in the Baltimore suburb of Owings Mills in 1986, the manuscript was greatly slimmed down, leaving many pages of outtakes I couldn’t trash outright. There was enough to create more novels, or so my inner trash picker insisted.

We’ll look at those as they took shape during my furious year of keyboarding on my new personal computer, however primitive the machine and process appear now.

In that sabbatical, I must say I was highly disciplined, keyboarding for four hours or so before taking a break, eating, even napping, and then returning to the work until two or so in the early morning. I had lived my adult life up to this point awaiting this moment, if it was far from what I had envisioned. Suburbs? Without a wife or soulmate? Heartbroken, in fact?

What drives an artist, anyway?

Beyond the yellow BMW 1600 oil-burning coup I was bopping around in – the one that was older than any of the women I was seeing.

A great deal of material and energy was there to be released, and I sensed this was my make-it-or-lose-it moment. As you’ll see.

Baltimore even had its own subway line under construction, reaching all the way out to where I was encamped.

Not that I would be there when it opened.

~*~

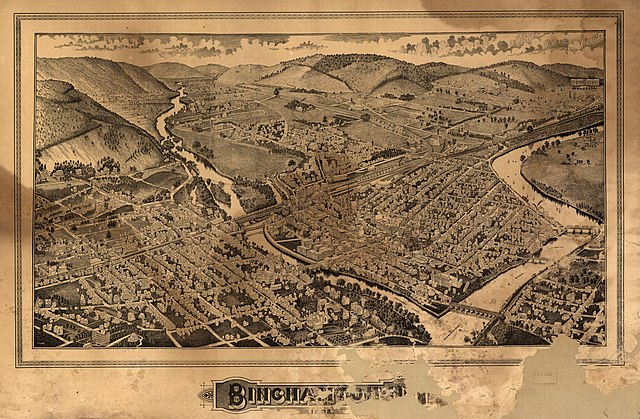

My first hick outpost, the one upstate, wasn’t as small as it seemed. Yes, it was a backwater, but the core was more populous than six of the places I would subsequently live in, if you didn’t count the university students in what I would dub Daffodil.

What my first actual job in journalism did have, though, was proximity to New York City, a mere 3½- to four-hour drive away. Despite the distance, the connection was vital, even vibrant. All of my new friends were from the Big Apple, and many of them were Jewish, as my college girlfriend was, even though she had by now oozed away from my presence, off on what I saw as troubling new places. At least none of them were Jonestown.

Starting with a summer internship before my senior year of college and picking up again after my graduation, a time of great emotional upheaval, exploration, and redirection. As I said, this was in the high hippie outbreak.

I presented the image that flashed before me, the gandy dancer who could have been a hitchhiker, but I should also acknowledge a freaky cartoon a housemate had created and handed me, with a face at a sewer grate mumbling “Duma luma, duma luma.” Those were the two prompts for the manuscript, seriously.

~*~

The inspiration also came from my first jaunts into New York City while living upstate, and later to the west in the Pocono mountains of Pennsylvania. Most of my buds and girlfriends had been from the City, as they called it. My early experiences turned into fascination during a period of great personal upheaval and growth for me.

Hippies seemed to be trying to go in two directions at once: back to the big city while hitchhiking out in the sticks. The original version was, in fact, published as Subway Hitchhikers in 1990 – the worst bookselling season in the memory of many publishers, thanks to the first Iraq war.

As I’ve ready described, in the 17 years between the first draft and the story’s first publication, the manuscript underwent a considerable metamorphosis as I moved across the continent in my day job. While living in the desert of Washington state, I even picked up a 1915 engineering book on the building of the New York subway system while browsing in a very small, small-town bookstore. (How did it ever land there?) Much of my expanding text was backstory on the central character, while the urban transit episodes shifted into something akin to an appendix. The result was an unwieldy epic. But I kept the outtakes, which took on their own life later.