I’ve mentioned my bewilderment at the failure by the Church of England to serve its communicants in New England during most of the 1600s.

As well as the fact that Dover’s First Parish could have been the first Baptist church in America, beating Roger Williams in Providence, Rhode Island, by a year.

What perplexes me is that I find nothing in New Hampshire before almost 1800, although there was a church in Boston, a place where Friends struggled.

The fact is that the Baptist tradition originated as a liberal movement. We’ve seen threads of that continuing in Jimmy Carter and Bill Moyers.

In my research, I kept coming across fleeting references to Baptists during the years before the American Revolution, but curiously not much outside of Rhode Island to indicate ongoing activity in New England. They were not singled out like the Quakers as great dangers to social or godly order, even though they were still outlawed and ridiculed. Did they meet secretly, perhaps even at times other than Sunday morning? None were hanged in Boston, for one thing. In New Hampshire, they had only three congregations by 1770 – Newton, founded 1755; Madbury, adjacent to Dover; and Weare, which had a strong Quaker presence. Still, as I sense, theirs is a crucial history yet to be written.

Considering all the furor around minister Hanserd Knollys’ brief tenure in Dover, just before he began preaching definitively Baptist doctrines, as well as the support he had, I keep wondering about his legacy in the Piscataqua settlement. Somehow, he set off an unorthodox flame in the community, at least by Puritan standards.

Curiously, as I considered the matriarchal role in the continuing nurture of a faith tradition, the path led back to Thomas Roberts and his wife, Rebecca Hilton. This time I chanced across not their Quaker impact but rather a Baptist one.

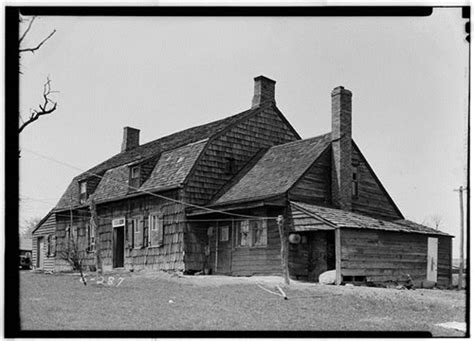

Their daughter Esther – also recorded as Hester and Easter – born around 1625 and one of the first English children in New Hampshire, married John Martin (also Martyn) around 1645 in Dover. He descends from Mayflower arrivals in Plymouth Bay. After a round of public service, they relocate to Oyster Bay on Long Island, perhaps among those who flee to avoid persecution, but in 1666 move on to New Jersey shortly after the British seized it from the Netherlands. Joined by Drake, Dunn, Gilman, Hull, and Langstaff families from New Hampshire, as well as other Baptist New Englanders, the name Piscataway soon sticks to their New Jersey community, reflecting their Piscataqua roots. Theirs was perhaps the seventh oldest Baptist congregation in America. The colony itself came under Quaker proprietorship in 1675, assuring religious liberty. Think about all that the next time you’re driving along the New Jersey Turnpike and see the signs for that exit.

That’s the last I find of Baptists in New Hampshire until a Scammon from Stratham on Great Bay – a surname that appears early among Friends – weds a Rachel Thurber of Rehoboth in southern Massachusetts in 1720. Resettling in Stratham, she struggles for 40 years, making one conversion, before moving on to Boston and being baptized into its second Baptist church.

Glory, hallelujah, and all that.

~*~

Welcome to Dover’s upcoming 400th anniversary.