It’s hard for modern Americans to understand a basic reality of European colonies in the New World.

None of the players in the story own the land they’re dealing with.

Not the settlers, even though they’re clearing it and building on it.

Nor the proprietors or investors, either. They’re more like developers who offer leasing opportunities. Think of rental agents.

Nor the Indigenous tribes, surprisingly, even though many of the settlers also negotiate a payment to them for their land. The use of their land, more accurately. Admittedly, the payments are largely symbolic – a bushel of corn a year, for example.

No, quite simply, all land “belongs” to the king, and he allocates the privilege of using it as a means of leveraging his own prestige and power.

Under the feudal system, that would mean grants to barons and other lords in return for their fealty.

They, in turn, could dole some out to knights, who then become wealthy, as well.

Add to that the gentlemen farmers, living off the rents to their estates.

And then yeomen, who are still free on their own tenants, as their small holdings were called.

And husbandmen.

And, somewhere below that, the serfs who are bound to the land and its holder. Well, by this point in time, they’d been freed but were still at the bottom of the ladder.

~*~

THIS IS THE MODEL OF LANDHOLDING – not landownership – up through the American Revolution.

Its assumptions are quite different from those of modern Americans. What do you mean? I don’t own the ground under my house and barn?

No, you don’t. And you still have to pay rent on it.

~*~

AS A FURTHER COMPLICATION, charters could be revoked or rewritten.

Falling out of the king’s favor would have costly and dire consequences.

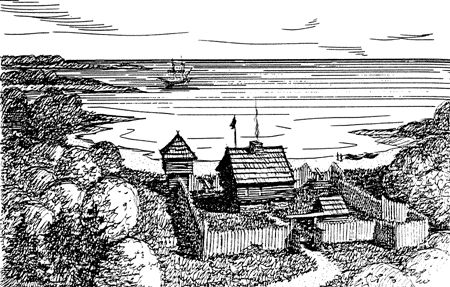

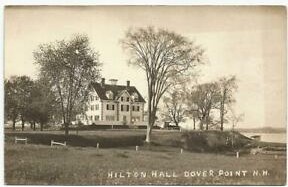

As my upcoming book describes, this land arrangement affected Dover and the rest of New England through a series of realignments and controversies and attempted evictions.

In fact, it almost leads to a rebellion in Boston Harbor against the king a century-and-a-half before Paul Revere’s midnight ride. Well, that’s one aside I don’t develop. There’s too much else going on along the Piscataqua.