THEY WERE “PKs,” meaning “preacher’s kids,” a difficult role for nearly every child put in its unwanted spotlight. Beyond that, theirs does appear to be a tight-laced family, even with its strong strain of moral and social progress. We can even wonder what the brothers’ diagnosis would have been today; there are speculations of “somewhere on the spectrum.”

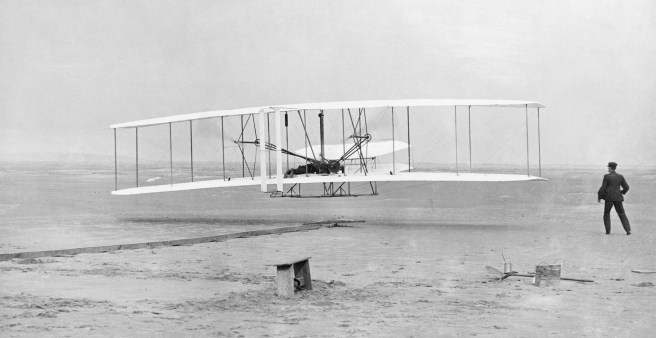

Still, they did put humans into the air and, more importantly, brought them down safely.

We’ll put their technological breakthroughs aside today and instead focus on the more personal surroundings of Wilbur (1867-1912) and Orville (1871-1948), sons of Bishop Milton Wright and Susan Catherine Koerner Wright.

Like me, they were both born in Dayton, Ohio, and we were members of a congregation their father had founded. (He also founded a seminary.)

And, gee, a photo of the house they grew up in looks almost identical to my grandparents’.

Here are ten more interesting points gleaned from the Web:

- Neither one graduated from high school. They were, however, friends of classmate Paul Laurence Dunbar, the school’s only Black student, now an acclaimed poet, and in time, at their print shop, they published a newspaper he created. Yes, they were printers and bicycle manufacturers before they built airplanes.

- They learned many of their mechanical skills from their mother, who had attended Hartville College, a small United Brethren school in Indiana, at a time when few women were permitted such an opportunity. Her focus, tellingly, was literature, science, and mathematics. In 1853, she met the future bishop. He had joined the church in 1846 because of its stand on political and moral issues including alcohol, the abolition of slavery, and opposition to “secret societies” such as Freemasonry, values she shared. Working together as his ministry developed, they brought their boys to 12 different homes across Indiana and Iowa before returning permanently to Dayton in 1884.

- A year or so later, while playing an ice-skating game with friends Wilbur was struck in the face with a hockey stick by Oliver Crook Haugh, whose other claim to fame would be as a serial killer. Wilbur lost his front teeth. Up until then, he had been vigorous and athletic, but the emotional impact left him socially withdrawn, and rather than attending Yale as planned, he spent the next few years largely housebound, indulging in the family’s extensive library and caring for his mother, who was terminally ill with tuberculosis.

- More befitting a PK, in elementary school Orville was prone to mischief, including practical jokes, and even expelled once.

- They weren’t the only Wright brothers. Reuchlin (1861-1920) was their oldest sibling. Born in a log cabin in Indiana, he grew into a restless young man, failed college twice, then moved to Kansas City in 1889, distancing himself from his family. He worked in Kansas City as a bookkeeper until 1901, then moved on to a Kansas farm with his wife and children to raise cattle. Though he built a good life for his family there, he remained estranged from the rest of his family in Dayton.

- Lorin (1862-1939) spent time on the Kansas frontier before attending Hartville College in 1882 and returning to Dayton, where he had difficulty making a living. So he left for Kansas City in 1886 (before his elder brother), struggled, briefly, returned to Dayton, and then headed west again, where he scraped out a living on the Kansas frontier for two years before returning home in 1889, lonely and homesick. He worked as a bookkeeper for a carpet store in Dayton and married his childhood sweetheart, Ivonette Stokes, in 1892; they had four children as he settled down to a quiet life. In 1893, he worked for Wilbur and Orville in their print shop, and in 1900 helped sister Katharine manage the Wright Cycle company while their brothers were in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. He visited Wilbur and Orville at Kitty Hawk in 1902, notified the press in 1903 after their first powered flights, and lent them his barn to build the machine that eventually became the first United States military aircraft. In 1911, he helped test the first airplane autopilot and in 1915, spied on Glenn Curtiss to gather information for the Wright patent suit against the rival airplane manufacturer. After Orville sold the Wright Company, Lorin bought an interest in Miami Wood Specialties, the company manufactured a toy that Orville designed. He also was elected a city commissioner in Dayton.

- Twins Otis and Ida (1870) died in infancy. He, of jaundice; she, five days later, of marasmus – malnutrition.

- Their youngest sibling, Katharine (1874-1929), could be the subject of a Tendril all her own. She was only 15 years old when her mother died of tuberculosis in 1889. As the only female child, it was taken for granted that she would assume her mother’s role—which she did – caring for the family and managing the household. She was especially close to Wilbur and Orville, and when her mother died it became her responsibility to take over the household, seemingly ending any prospects of marriage. Yet she also graduated from Oberlin, at the other corner of the state, in 1898, the only Wright child to complete college. She then became a highly respected teacher at Dayton’s Steele High School. After Orville’s injury in a 1908 test flight for the military at Fort Myer, Virginia, she took a leave of absence from her teaching job to nurse him back to health and never returned to teaching. Instead, she became a central figure in her brothers’ aviation enterprises. In 1909, the French awarded her, along with Wilbur and Orville, the Legion d’Honneur, making her one of the only women from the U.S. to receive one. After Wilbur’s death in 1912, Orville became more and more dependent on Kate, as his old injuries had him in severe pain. She looked after his correspondence and business engagements along with his secretary, Mabel Beck, and ran the household as before. In the 1920s, Kate began to renew correspondence with an old flame from her college days, a newspaperman named Henry Haskell, who lived in Kansas City. (What is it with Kansas City for this family?) They quickly began a romance through their letters, but she feared Orville would become jealous. After several attempts, Henry broke the news to Orville, who was devastated and refused to speak to the couple. When they finally wed in 1926, Orville refused to attend the ceremony, and wouldn’t speak to them up until they moved to Kansas City. She was ridden with guilt for choosing Henry over her brother, and tried many times for a reconciliation, but Orville stubbornly refused. Two years after her marriage, Katharine contracted pneumonia. Even when Orville found out, he refused to contact her. It was their brother Lorin who eventually persuaded him to visit her on her deathbed, and was with her when she died. She was 54.

- None of the Wright children had middle names. Wilbur and Orville were “Will” and “Orv” to their friends, and “Ullam” and “Bubs” to each other.

- The parents and siblings, minus Reuch, are buried at Woodland cemetery in Dayton.

For a broader view, let me suggest The Bishop’s Boys: A Life of Wilbur and Orville Wright by Tom Crouch.

The United Brethren denomination also figures prominently in my posts at Orphan George.