No matter how gonzo the narrative, my novella With a passing freight train of 119 cars and twin cabooses is sounding more truthful than some of the political candidates.

To see how, click here.

You never know what we'll churn up in cleaning a stall

No matter how gonzo the narrative, my novella With a passing freight train of 119 cars and twin cabooses is sounding more truthful than some of the political candidates.

To see how, click here.

In the buildup of national elections, once again a major influence remains the elephant in the room. I’m referring to the legacy – make that plural, legacies – of the hippie outburst, especially in contrast to those on the Vietnam war side of the divide.

The wounds and tensions haven’t gone away. Just look at the continuing proliferation of POW-MIA black flags across the landscape, on one side.

For the other, the lines are much more hazy yet festering. As I’ve been arguing, hippies came – and still come – in all varieties and degrees, and likely nobody ever fit what’s become the media stereotype. With the end of the military draft, the movement lost a crucial motivating force and focusing definition.

Complicating the situation was the distancing many youths on the antiwar side felt when it came to politics. With its support of the military at the time, liberal politics were tainted with outdated Cold War ideologies like those of the conservative side. For hippies, radical was the label of honor. And the Democratic Party base of the left was splintered as its youthful potential allies had nowhere to turn or direct their forces in the political arena.

The horror meant going from a hawkish LBJ administration to one of Richard Nixon.

Fast-forward now to the present American landscape. Gone are the grandparents and parents of many of the now senior baby boomers – the core of the hippie movement versus the older generations. Yet political candidates still tiptoe around many of the reality issues, beginning with marijuana and other illicit substances, as if they’re too hot to touch. Let’s get real. Want to talk about litmus tests?

As we look at candidates, ask where each stands on a scale of continuing issues from the hippie stream. I find it enlightening.

Well, we have Bernie running straight true to the cause. Hillary, more cautiously so. But on the right? Let me suggest being wary of anyone in the pro-war camp who hasn’t served. Period. As for other life experiences?

~*~

All of this returns me to my Hippie Trails series of novels. I’d love for you to come along. Just click here.

No matter how trippy the narrative, With a passing freight train of 119 cars and twin cabooses is sounding more realistic than some of the political candidates.

To see how, click here.

Decades ago, after hearing mention that my family had Quaker roots in North Carolina, I began the genealogical detective work that now fills my Orphan George Chronicles. Although I’d independently come to the Society of Friends and become a formal member, I was surprised to hear that my family had been Quaker and that there were Quakers in North Carolina – my, have my eyes been opened!

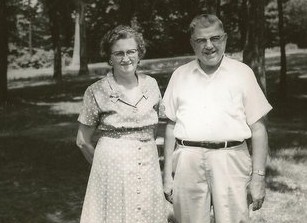

In the genealogical work, I chose to begin with my great-grandparents – people I’d never met in the flesh.

But when my father died, the focus shifted. I realized only one person remained who might be able to fill me in on questions of his childhood and parents, and that was his “baby sister.” That would mean getting to know her – and her parents – without all of the filters that had always been applied by my mother, who had issues of her own. (Oh, for these family dynamics!)

It became a rich and fascinating project, given all the more incentive when we met my aunt and her husband, a retired university dean, at the airport. It was a first-time encounter for them and my brood, yet he swept up my younger one in his arms and proclaimed, “It’s so good to have another Democrat in the Hodson family!” The party activist suddenly had a favorite uncle. Make it great-uncle-by-marriage if you will, he got the crown.

At that point, my aunt remarked that Grandpa’s slogan, painted on all of his trucks and on the calendars he mailed out each year, was “Dayton’s Leading Republican Plumber.” She promised to send a photo of the vans all lined up on the street. “You didn’t know that? It was even on his stationery and bills.” This was something I’d never known, although he did sign one of his last notes to me as “formerly Dayton’s leading Republican plumber,” a comment that long puzzled me. Through much of the spring and summer I wound up following up on her reactions and insights to her childhood and adolescence, which to my surprise (the word of the day) paralleled my own, especially in regards to their now-Methodist church, the denomination I grew up in. At last, I could finally look directly at my grandparents through all the memories and scattered bits of data I could assemble, as well as all the material I already had, doing genealogy. It was like being given a key, at last.

My aunt suggested I correspond with a surviving first-cousin Dad’s age, who wound up also contributing memories, and the result was a remarkable project, not quite memoir but more a realization of finally knowing my grandparents, pro and con, for the first time – years after their deaths – as well as questioning many of our ingrained expectations: just what are grandparents supposed to be, do, or look like, for instance. Unexpectedly, I reconnected to more feelings/memories from their house on McOwen Street than to the house I grew up in on Oakdale Avenue. Some of the stories that turned up, like my dad’s desire to be a sports writer or a big chicken dinner Grandpa arranged to help pay medical bills for one of Mom’s best friends, are priceless. From an intellectual perspective, the project also illuminates the difficulty of knowing – it often meant triangulating something in the middle of three often contradictory sets of perceptions. More importantly, to some extent, I’ve finally been able to reconnect with more than a few fragments of my childhood.

From my end, there’s little I’d say was happy in all of that childhood. But there are things I can finally claim and appreciate, and even rework or rewire. Much of my adult life, as I’ve found in Dad’s genealogy (Mom’s is entirely different, and far more gothic than she ever would have admitted) has been a matter of reclaiming many of the values and practices Grandma and Grandpa rejected in their move to the up-and-coming industrial city. I never knew that my Hodson ancestors were Quaker or that Grandma’s were Dunker (Church of the Brethren), very close to Amish and oh-so Pennsylvania Dutch. But they rejected all that, with some values somehow surviving, however invisibly.

Some discoveries still amaze me. The fact that Grandpa accomplished all he did with nothing more than a grade-school education, for one thing.

Or that his two best friends in adulthood were both a decade older than himself, and both died within a year – one of ALS, the other in a car collision. Since he was the youngest of three sons, I wonder about the dynamics.

There’s much, much more I’ve uncovered along the way. As you can guess, it’s a long story. Today would have been his birthday.

No matter how wild the narrative, With a passing freight train of 119 cars and twin cabooses is sounding saner than some of the political candidates.

To see how, click here.

It’s not the first time I’ve read it this way:

It feels all so fitting for a suburb.

Think of passenger rails and unless you’re a rare daily commuter, you’re likely to envision earlier eras. Steam powered locomotives, for starters.

And then great journeys across the landscape.

Now keep going. Deeper into history. Trips onto the frontiers of knowledge. The edge of the known world.

You might run into genius in the most unanticipated haven.

Like this.

For your ticket, click here.

From the rails, the landscape threads together quite differently than it does from a highway or water passage.

The tracks pass sidings, graffiti-tagged warehouses and low factories, storage yards of all varieties, rundown housing, apartment clusters – and once out into the farmlands, grain elevators as well.

Clicking along, you can’t help but wonder how many of the enterprises are legit or how many, in their decrepitude, cover questionable activities.

For a maverick intellectual gone incognito, they might even be an ideal location to go underground for a while – a place to work uninterrupted.

In my novella With a passing freight train of 119 cars and twin cabooses, English Bible translator John Wycliffe shows up in a railroad crossing on the American Great Plains, where he’s soon joined by Hieronymus Bosch.

As they discover, once you’re lost in time and space, anything just might happen.

~*~

For more of the fantasy, click here.

For more of the fantasy, click here.

A young organist once mentioned that he doesn’t listen to music the way some of the rest of us do. While I’m usually aware of the time signature, or at least a basic pattern to beat, much more than that fills his awareness. We could begin with the key or chordal progressions or structural development or phrasing. As for emotions? Way down on his list.

Of course, something similar happens for me as a reader. The author looks at much else besides the story, as reading reviews of Jeffrey Eugenides’ Middlesex reminds me.

I’ve already mentioned that my primary interest was in its presentation of Greek-American life. These aren’t celebrities or university professors or artists but people trying to survive the economic challenges of everyday existence. He does so in a matter-of-fact way, with a darker view of humanity than I’d usually take but more accepting of their foibles and failures, too. Everyone’s flawed. He’s not afraid to reveal the villains among them, family or not. If only I could revisit my own Sunday dinners with such cold accuracy! (The skeletons in my family closet, from what I can tell, are much further back and mostly in my mother’s ancestry. But the dysfunctions, well, that’s an entirely different matter.) To put his accomplishment here in a different light, his details are both particular and universal. They hit close to home. If only we had terms of affection like Dolly mou, which I take to be a variation on Koukla mou. Or, for that matter, if we were only so outwardly open and affectionate, period.

The novel’s more prominent theme, Cal’s sexual identity, advances in good taste. Nothing salacious but rather an ongoing, almost innocent discovery by narrator and reader alike. Eugenides manages the rare accomplishment of being a male who writes a convincing female character from within. In fact, he gets close enough to have had me wondering if were writing autobiographically of his own condition. That, alone, is astonishing.

As I was reading, I wasn’t yet aware of his reputation as a short-story master, but it makes sense. Much of this novel builds as shifts between stories separated over time.

Technically, his use of point of view is amazing. His Virgin Suicides was acclaimed for its daring use of first-person plural. Here, though, he mixes first-person singular, with its immediacy and intimacy, and third-person, with its semi-omniscient awareness, sometimes in abutting sentences, so that you get a stereoscopic view at once from within and without. Through the first half of the book, especially, much of this happens before Cal’s birth, which creates a kind of time travel. And it works. How much of the related details are “real” and how much merely imagined by the narrator, we should note, remains up in the air. But it’s effective, all the same.

Eugenides’ presentations of the massacre by the Turks and later race riot in Detroit are masterful and moving.

Throughout, the factual accuracy feels right. He’s done his homework and often conveys complexities with a few confident brush strokes. His insights on Eastern Orthodox Christianity are especially notable that way. As for his takes on hippie experience, I’ll simply say, Ouch! As I said, he often takes a darker view of humanity than do I.

Another major subject is his corner of the American Midwest. Contrary to common opinion, the region is hardly homogeneous and is anything but compact. Ohio, for instance, is the size of England. Presentations of it in contemporary literature are surprisingly rare, at least in proportion to the population. And there are many variations in the underlying cultures and outlooks. Kurt Vonnegut’s Indiana, for one thing, is quite different from Saul Bellow’s Chicago – and neither of them resembles what I know of Eugenides’ locale, Detroit. (Let me add my own emphasis on the importance of place itself to the extent it might be considered a character within much of my writing.)

What Eugenides presents is a more compact metropolis than I remember, but definitive in a blend of influences I recognize across much of northern Ohio and Indiana as well. Whether dealing with the older inner city, which then leads into issues of race and racism, or later suburban life, the descriptions resonate with what I found throughout the industrial Rust Belt. Cal’s grandfather’s encounters with Ford Motor Company’s melting-pot police or Cal’s father’s dealing with the real estate point system quickly demonstrate the cost of maintaining a unique identity. You didn’t have to be an immigrant to run afoul of that, either, I’d add from another direction.

It’s not a “perfect” novel, but nothing this ambitious could be. As the Detroit Free Press review expressed, “What Dublin got from James Joyce — a sprawling, ambitious, loving, exasperated and playful chronicle of all its good and bad parts — Detroit got from native son Euginides.”

For me, a drift sets in late in the volume with the introduction of the Desired Object and Cal’s sexual desire awakening. The tight construction seems to be coming apart, sprawling, but! In retrospect, it’s more that a second novel is taking off with leaps to Manhattan and then San Francisco before coming to a powerfully focused and moving conclusion.

So here I am, full of admiration and wonder. How does he pull this off? Where do those brilliant flashes of humor spring from? How does he make some essentially unsympathetic characters come to life in daily survival?

He plays throughout the story with Cal’s grandmother’s skillful touch with silkworms and the ways their silk reflects events around them. It’s one more stream of knowledge that runs like a thread holding the work together.

Eugenides, then, may be seeing himself as a silkworm issuing the long, long filament – for that matter, a nearly endless stream of organ chords – or, as we’d say, spinning a yarn.

Somehow, it all fits. Marvelously.