While the 100-acre Shackford holdings along Water Street underwent subdivision and real estate development, the 100 acres at Shackford Head remained intact. So far, I’ve been unable to locate the original title that would have been bestowed by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts to Captain John Shackford senior, but the documents for the adjacent Coney or Cony Farm repeatedly refer to the land held by John Shackford, during his life, or later, “land formerly of John Shackford.”

In 1837, when Joseph Coney leased his 40-acre farm to his son, Samuel May Coney (1812-1895), the rent was recorded as one cent a year.

Samuel soon came into full possession. By the time of his death, he had added the Shackford property, too, as was noted in the sale from the estate (attorney John H. McFaul) to Charles O. Furbush in 1896. That transaction included an 1895 Plan of Shackford Head by surveyor H.R. Taylor.

All of this would become part of the controversial attempt of Pittston Company’s attempt to build a massive oil terminal and refinery on the site in the 1970s.

I can see why Shackford heirs living in Eastport would have held onto the rugged land. A house could go through 40 cords of firewood in a year, and with seven homes or more at times, having a large wooded reserve would have been useful. Depending on the proximity of a sawmill, the wooded land could have also supplied the Shackford shipyard or even the wood in our house.

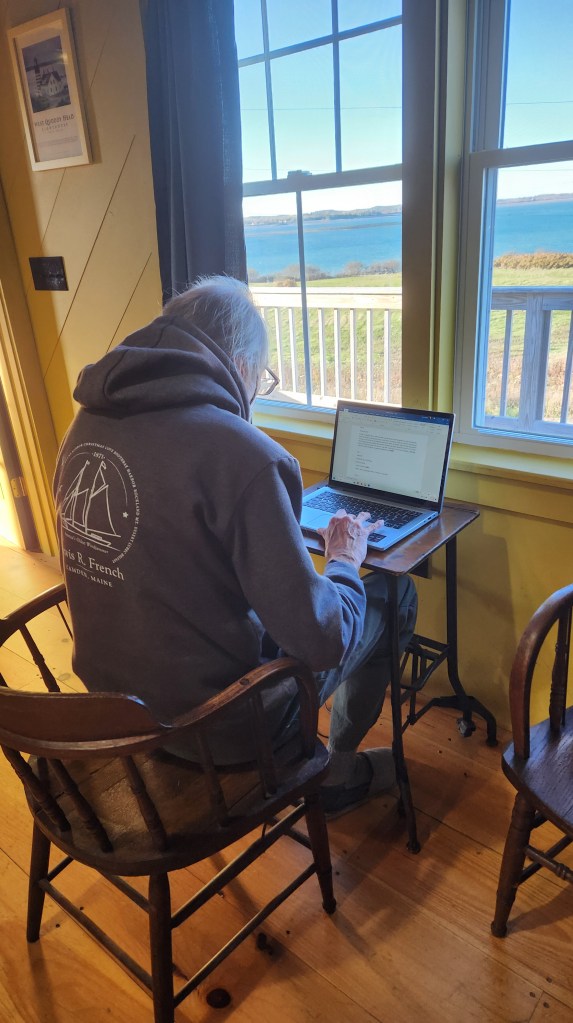

Here I am at the keyboard while overlooking Lubec Channel from a rented cabin at West Quoddy Station, a former U.S. Coast Guard lifesaving post. We needed to vacate our home for two days during its renovation, and we settled on this, still in sight of Eastport on the water to the north and yet a world away.

Here I am at the keyboard while overlooking Lubec Channel from a rented cabin at West Quoddy Station, a former U.S. Coast Guard lifesaving post. We needed to vacate our home for two days during its renovation, and we settled on this, still in sight of Eastport on the water to the north and yet a world away. As seen from a cruise aboard the historic schooner Louis R. French on Penobscot Bay last summer.

As seen from a cruise aboard the historic schooner Louis R. French on Penobscot Bay last summer. I just missed a shot of two eagles. A week later, with the water higher, I watched two harbor seals at play. Cobscook Bay is less than a mile downstream.

I just missed a shot of two eagles. A week later, with the water higher, I watched two harbor seals at play. Cobscook Bay is less than a mile downstream.