Look for my books, sharply discounted. A few are even offered for free.

You never know what we'll churn up in cleaning a stall

Look for my books, sharply discounted. A few are even offered for free.

In my revisions of the novel Daffodil Sunrise into a more sweeping Daffodil Uprising, I added backstory involving Indiana politics and efforts to extract personal wealth from one of its state universities.

Considering the current effort of the governor to seize control of the school’s board of trustees has me realizing my dark imaginings were all too naïve.

We know what one-party rule did in Germany and also in the Soviet Union.

In my book, the administration had little interest in listening to the students, much less in responding to their needs.

You can bet that will be a renewed breakdown ahead.

Indiana sometimes shows up as a symbolic state. It’s not just a “crossroads of America,” as it likes to tout itself, a blending of North and South or balancing East versus West. It’s an anomaly even in the Midwest, where it’s the only state not bearing an Indigenous name yet it’s named in supposed homage to the Original Peoples – INDIAN-a.

With a capital called INDIAN-apolis. Or Naptown, as it’s known in other parts of the state.

Not that there are any tribes remaining within its boundaries.

It’s not as industrial as Ohio or Illinois nor as agricultural as, say, Iowa or Minnesota – feel free to counter that with hard data, I’m just running on gut feeling here.

And just what is a Hoosier, anyway? There are theories, but it’s certainly not like a buckeye or hawkeye or badger or the Bluegrass State bordering its south or Prairie State on its west or Great Lakes State on its north. You can get a picture in your mind with those.

In short, it rather strives to appear just average, or maybe a level just below. Somehow, that’s what fuels its role as a symbol of America itself, especially the Bread Basket sprawling largely westward, even though it’s rarely in the spotlight, except for Indy 500 week, and even that reflects an earlier glory.

That wasn’t always the case, though. The place gave birth to some leftist progressives over the years as well as some vital inventors. It also gave us the likes of journalist Ernie Pyle, jazz lyricist Hoagie Carmichael, actor James Dean, radio storyteller Jean Shepherd, basketball great Larry Bird, rocker John Mellencamp, late-night host David Letterman. But no U.S. president.

Early on, it had a heavy Southern influence, especially as Quaker families fled the slaveholding economy of North Carolina, as I learned after taking up genealogy and uncovering my roots.

It also has some distinctly different regions, including the once dominant steelmaking crescent along Lake Michigan adjacent to Chicago; the hardscrabble rolling forests and quarries of southern Indiana; and the flat agricultural belt in the middle.

I got to know it first by family camping trips and Boy Scout overnight hiking excursions. Yes, in the southern tracts of the state. We also had journeys when my great-grandmother decided to visit from Missouri or central Illinois; her son and his wife lived in a dreadful corner of Indianapolis and served as the relay point. Later, I finished college, again in the rustic south, and returned four years after as a political science research associate.

I must admit my angst at what’s been happening politically and socially, even though the Indianapolis Star was always a pretty dreadful archconservative voice, proof for me that “liberal” journalism has always been in the minority.

~*~

Not that the state hasn’t had an artistic presence. Just think of the artist Robert Indiana of the iconic LOVE image (born in New Castle).

Novelist Kurt Vonnegut nailed the state for me, though other writers of note include Booth Tarkington, Theodore Dreiser, Ward Just, New Yorker regular Janet Flanner (from Paris), and young-adult superstar John Green. The poets Clayton Eshelman, with his collection Indiana, and Etheridge Knight also have had strong careers.

For my part, my novels Daffodil Uprising and What’s Left are both based in an imaginative reworking of Bloomington – I do play with geography, making the Ohio River a lot closer to Indianapolis, for one thing. My novel Hometown News could also be placed in the upper half of the state, though its setting is more generalized.

My poetry chapbook Leonard Springs definitely reflects the cave country around Bloomington.

I anticipated remaining there much longer than I did, but fate intervened. And after that, I’ve never been back, except in my memories.

When we think of many of the technological advances that impact our daily lives, we usually don’t know the names of their inventors, even when we know the businessmen who got wealthy as a result. Elon Musk did not invent the Tesla, for instance, nor did Bill Gates invent the internet or Henry Ford, the auto. The list is actually a long one.

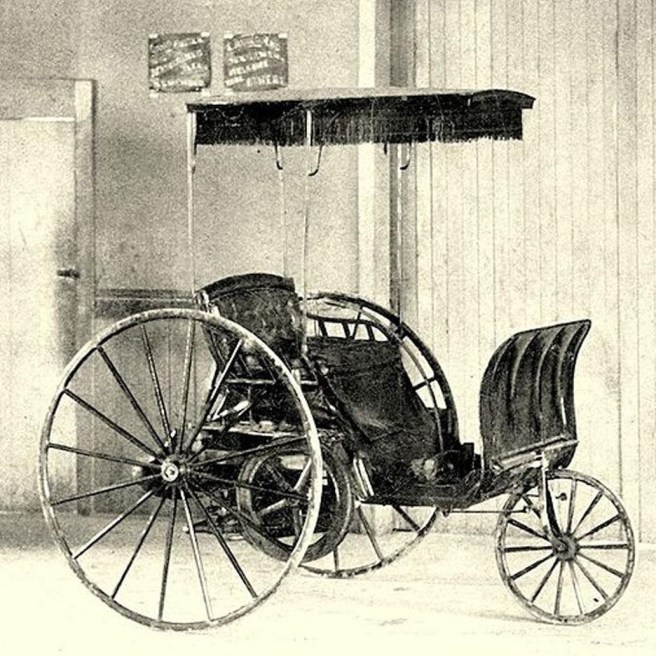

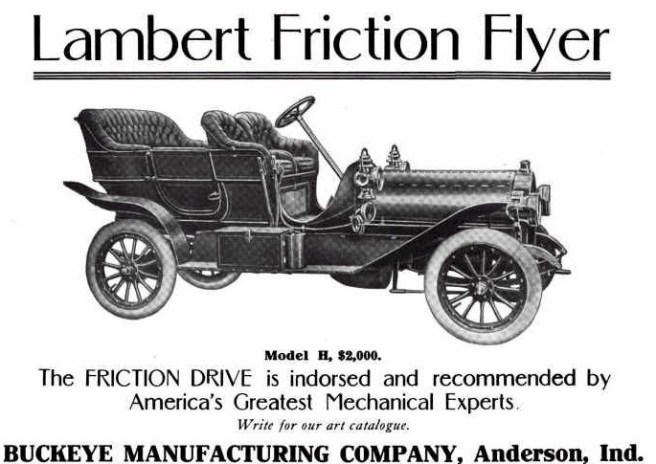

Consider John William Lambert, mentioned in a previous Tendrils.

I remember visiting an early coworker and, upon seeing an old car with an impressive Lambert name in brass across the radiator sitting at an open garage door, I asked, “Ann? Is that car any relation to you?” She replied that her grandfather used to make them but otherwise conveyed no knowledge that he had been so prominent a figure.

Here are ten facts from his life.

Let’s consider fourth place, as far as length in time. That is, realizing that I’ve been dwelling in Eastport four years now strikes me as a bit of a shock. I’m finding it difficult to make sense of the fact, at least in light of earlier landings.

Quite simply, I’m still settling in here, even if it’s in my so-called sunset years. And, yes, I’m still feeling this is it, a very suitable end of my road, even if I am being greeted by name by people I don’t recall knowing, this is in sharp contrast to earlier locales.

For perspective, those shorter spans were in my early adulthood: Bloomington, Indiana (four years in two parts); Binghamton, New York (1½ years, in two parts and three addresses); the Poconos of Pennsylvania (1½ years); the town in northwest Ohio I call Prairie Depot (1½ years); Yakima, Washington (four years); a Mississippi River landing in Iowa (six months); Rust Belt in the northeast corner of Ohio (3½ years); and Baltimore, my big-city turn and turning point (three years). You’ve likely met many of them in my novels and poems.

Looking back, each of those addresses was filled with challenging turmoil and discovery, soul-searching yearning as well as glimmers of something more concrete and fulfilling just ahead.

In contrast, my longest period of living anywhere was Dover, New Hampshire (21 years), my native Dayton, Ohio (20 years), and Manchester, New Hampshire (13 years).

As the calendar year ends, it’s fair to ask What’s Left in your own life as you move on for the next round.

In my novel, the big question is stirred by a personal tragedy, leaving a bereft daughter struggling to make sense of her unconventional household and her close-knit extended Greek family.

In the wider picture, she’s faced with issues that are both universal and personal.

For me, it’s somehow fitting that my most recent work of fiction returns to Indiana, the place where my first novel originated before spinning off into big city subways. The state is also home to more Hodsons than anyplace else in the world, as far as I can see, not that I’ve been back in ages.

What’s Left is one of five novels I’m making available to you for free during Smashword’s annual end-of-the-year sale, which ends January First.

Get yours in the digital platform of your choice, and enter the New Year right.

For details, go to the book at Smashwords.com.

The four years covered in my novel Daffodil Uprising brought about tremendous change in the nation and around the globe. In the light of recent events, a fresh overview of the period may provide some essential perspective on current events. For some readers, it may even be a stroll down a Memory Lane of an activists’ protest march. Maybe you remember or maybe you’ve just heard of it as ancient history. In my story, the Revolution of Peace & Love unfolds at the crossroads of the America, where it never got the attention it deserves.

This week, you can still get the ebook for FREE during Smashword’s annual end-of-the-year sale, which ends January First.

Act now, before the deal ends, and you’ll have Daffodil Uprising to read in the digital platform of your choice for as long as you like.

For details, go to the book at Smashwords.com.

Cassia would have to say she’s in a big happy extended family, but she would disagree with

Tolstoy on his other point. Hers is not the same as any other. As for the unhappy part, she carries a world of grief after the disappearance of her father in a mountain avalanche.

My novel What’s Left follows the bereft daughter in her quest for identity and meaning over the decades that follow. Bit by bit, she discovers that he’s left her far more than she ever would have imagined, in effect guiding her to some pivotal choices.

The ebook is one of five novels I’m making available for FREE during Smashword’s annual end-of-the-year sale. Pick up yours in the digital platform of preference.

Think of this as my Christmas present to you. How can you not be interested in insights about family, especially at this time of year? Even if this one does have some Goth twists, probably unlike yours.

For details, go to the book at Smashwords.com.

Celebrity writer Tom Wolfe lamented that nobody had written the big hippie novel, something akin to the Great American Novel, but he was wrong. I’ve said so in some previous postings here.

For my part, let me invite you to Daffodil, Indiana, as its tranquil – some might even say dopy – campus goes radical. No outside agitators are needed in the face of the ongoing repression. The Revolution of Peace & Love is its own calling.

Daffodil Uprising is one of five novels I’m making available to you for FREE during Smashword’s annual end-of-the-year sale. The ebook is available to you in the platform of your choice.

Think of this as my Christmas present to you. Or, as we used to say, If it feels good, do it!

For details, go to the book at Smashwords.com.

A high school English and photography teacher, Pfingston also found himself at the center of an off-campus poetry circle that produced the annual review Stoney Lonesome, named for a small town near Bloomington, Indiana.

His own work, often reflecting family and neighbors and the rolling wooded nature of southern Indiana, are wonders of bejeweled focus and clarity on a passing time and place.

The directness is something few others achieve. Maybe Rumi comes closest, in a different way.