By the time the ebooks were published, I had remarried and settled into our little city farm on the New Hampshire seacoast, the one with the red barn that gives this blog its name. My life had stabilized and my job wasn’t devouring me alive, unlike my previous lower-level management positions.

But something kept nagging at me. I wanted to know just where the hippie movement had gone. Many of the insights have been posted here at the Red Barn, and I did draft a series of essays – Hippie Hopscotch – for a book competition that was cancelled after I sent my entry off. My conclusion is that the hippie impact is still around in many varied streams, much of the legacy taken for granted in contrast to the mass-media stereotypes or the current teens’ perception of hippie as being a girl thing. My wife and stepdaughters kept asking about the era and were astounded to hear just how much had changed for the better because of it. They were incredulous at the restrictions I had faced. Were things really as bad as Mad Men presented them? Yes, and the show had me retasting the first newspaper I worked for, the one that came closest to major metro. I mean, I could almost smell it.

Could any of this earlier work be salvaged? And what could I do with the searing childhood betrayal piece published online in Hobart?

My first published novel, Subway Hitchhikers, had ended with Kenzie’s return to Indiana. Intuitively, I had him, as a Tibetan Buddhist lama reincarnated into Iowa, marrying into a Greek-American family in Daffodil. I saw it as a way of blending two streams of ancient wisdom – one Asian, the other at the origins of Western culture. Something still felt incomplete in that ending.

Rather than trying to pick up the story with Kenzie himself two decades later, I decided to shift the focus to the next generation, which led me to create a daughter. This would be her story. As an added twist, I decided to have her lose him, not to divorce but an avalanche in the Himalayas, when she was just 11.

Unlike my earlier fiction, this one was undertaken totally in my retirement years. Yes, I had the ending of Hitchhikers as my prompt – and, based on that, some characters and a setting to work from – but this book would be done with fewer external demands than I’d faced in working on the others in my “spare” time.

Surprisingly, this became the hardest of all to bring to fruition, undergoing nine thorough revisions. In one version, there were no quotation marks. Another changed the tenses.

No quotation marks? Since she was relating the story anyway, including what other people had told her, who knows how accurately she repeated them. Blame Cormac McCarthy as a bad influence there. It was one flash of brilliant inspiration that ultimately proved confusing. Now, how many quotation marks did I eliminate in one sweep and how many did I have to insert as repairs? Both times, it involved a lot of keystrokes.

The focus shifted greatly, too.

At first, it was on what she uncovered about her father and his times. He was a hippie, after all, so we would see the hippie scene through her perceptions of his photographic record of people and events. In the next revision the focus turned to what had attracted him to join her extended family, one so different from his own roots. That led me to questions of just what a family is – a pretty slippery concept in today’s America – and then an examination of Greek-American culture in the Midwest itself. Finally, the focus was entirely on her, period, starting with her stages of adolescent grieving and emotional recovery.

I was a bit spooked when she began talking to me through my fingers as I was typing. She was snarky, too. Talking? She was dictating. Even scarier, she sounded a tad like my younger stepdaughter.

And it wasn’t just when I was up in my third-floor lair. Sometimes she talked to me while I was swimming laps or weeding the garden.

At some point this was no longer about a distant past, in her eyes at least, even when those roots impacted the present and its conflicts. By now, I was watching her grow up with each revision as she gained a snide, seemingly cynical tone and a goth appearance. I wish I had answers or at least advice for where she and her generation of the family wind up at the end of the book, but we do know what their options are.

The book also evolved into a multigenerational affair, reaching back to her great-grandparents and later jumping ahead to her nieces and nephews within a large, tightly knit extended family.

How to structure this baffled me until I came upon the way Jonathan Lethem handled a multigenerational novel that built on four sections of four chapters each, like a mosaic. Mine has five generations at play, once you include Cassia’s nieces and nephews, but the structure holds. Somehow it works differently than the traditional chronology of twenty-some chapters.

One of the 16 chapters, the subway ride to the Brooklyn art museum and its Tibetan galleries, comes from a lengthy outtake from a Hitchhikers draft, this time two or three decades later with Cassia, the daughter, rather than her father.

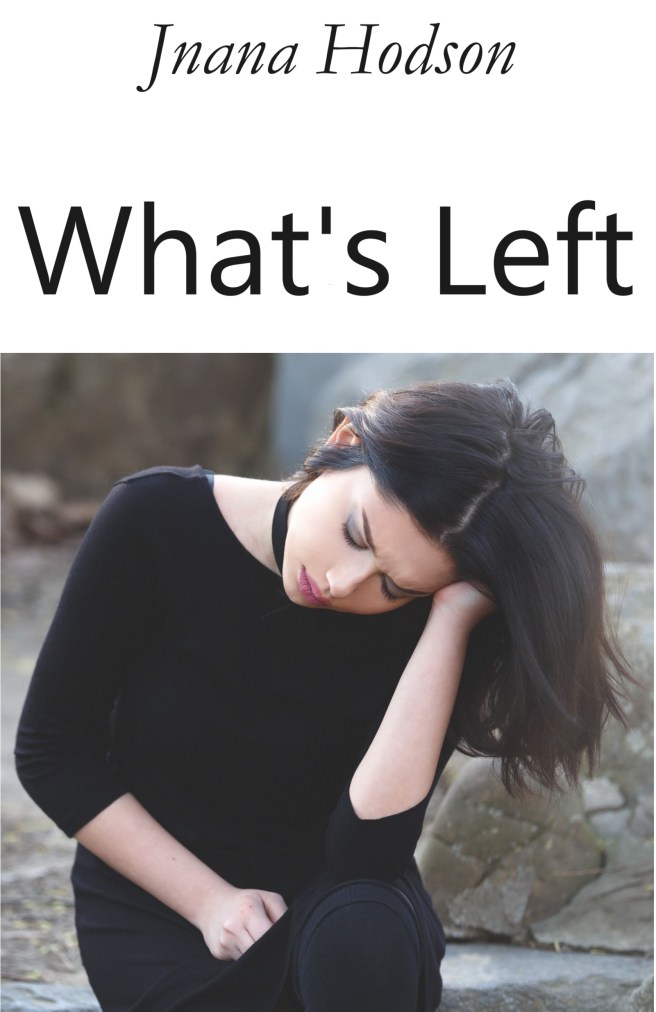

I should also admit that the title remained elusive. One I liked, Cassia’s Quest, got shot down for sounding more like a space journey. Another, in desperation, Diana’s Daughter pushed Kenzie out of range. What’s Left results as a double entendre, addressing both her situation and the manuscript itself.

Finding a suitable cover image was equally challenging. I liked a failing egg yoke as a reference to her being broken open and to her family’s restaurant. Photos of a grieving child or young woman never quite fit the physical description in the text itself and also failed to reflect the span from early adolescence into her 30s.

~*~

The project also had me reconsidering my own experiences.

Was I really ever a hippie? In my promotions for the novels, I contended that we came in all varieties and nobody fully fit the stereotype. That was, in fact, a central thrust of my novels, even when hippies are nowhere to be found, as was the case in Hometown News.

In the background, the local Greek Orthodox church opened the faith and culture to my curiosity. As I’ve discussed in posts here at the Red Barn, what I encountered was quite different from my Quaker simplicity but definitely enriched it, not just theologically but as in the traditional dancing, music, and food.

It was a good thing that I didn’t encounter the novels of the masterful Jeffrey Eugenides until after What’s Left had been published. I would have been too intimidated otherwise.

In addition to Jonathan Lethem, writers of inspiration during this project included Poppie Z. Bright, Anne Rice, and John Irving.

~*~

Not only was this the most difficult of my novels to writer, with deep revisions, but the central character, the snarcastic Cassia, had me rethinking everything that had gone before. She ordered me to revise the earlier books. Or else?

One of the advantages of ebooks is that new versions can be published rather easily. In this case, as you’ll see, she had my hippie books getting new titles, many characters getting new names, and many of the stories themselves being vastly enhanced.

All from what I jokingly called my culminating novel.

And that was before I returned to the others.

Here I had finally found myself in my goal of being free from the newsroom and having time to focus more fully on my “serious” writing. I just didn’t imagine it like this.

I still held a fondness for the hippie movement and its hopes but could clearly admit I had moved on. That part was liberating.

I’m still looking for that better world, though, as you know.

So here I was, back to the drawing board.