The second son of John senior and Esther was William, who “went to sea as a boy and continued to be a sailor all his life,” as the family said. Or maybe not quite that long. He did retire to land, as you’ll see. “He commanded the Active in 1807 and was subsequently master of the Sally, Orient, Blockade, and Five Brothers, ships largely concerned in the West Indian trade.” Naming the Blockade, by the way, sounds like an act of defiance, don’t you think? And Sally would have been a nickname for his first wife.

As a sea captain, he frequently ventured far from Eastport. As we’ve previously mentioned, at age 29 he was captured by French pirates off the coast of Spain, eventually ransomed, and made it back to Maine just before the British blockaded the American Atlantic coast during the War of 1812.

As related in another account, “He was in command of the brig Dawn when that American ship was captured by a French cruiser during the war with the French in the time of Napoleon I. He was carried to France, and upon being relieved at the instance of the American minister, he went to England and came before the mast as an ordinary seaman. He next commanded the Lady Sherbrooke and then the Sarah. His last vessel was the Splendid, a fine packet engaged in the freight and passenger traffic between Eastport, Portland, and Boston. He retired from sea service in 1833 and engaged in mercantile pursuits with his brother, Jacob.” More specifically, the firm was W. & J. Shackford & Company, merchants, shipbuilders, and fishermen. Lorenzo Sabine was a partner briefly enough to explain the “and company.”

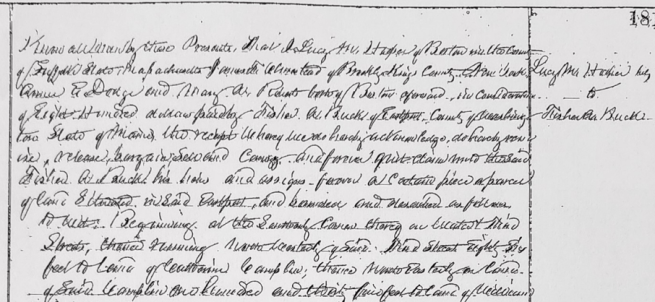

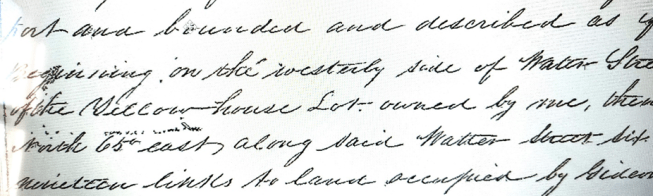

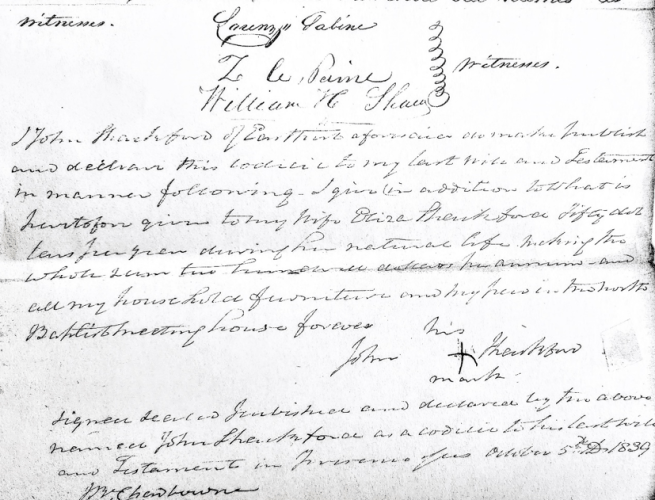

The retirement from sea service came around the same time the Shackford siblings surveyed their shared land holdings and began dividing it. There was much wheeling and dealing among the siblings and their nephews and nieces in the years that followed. Between 1840 and 1849, for instance, William sold or transferred or traded 33 parcels, including six to his brother Jacob.

William’s home at 10 Shackford Street is one block up and a block over from ours. Like others in the neighborhood, it was remodeled as styles changed. Parts of the structure may date to the early 1800s, while the front part of the house has the symmetry and simple lines common in area homes in the 1830s and ’40s. Much later (after his death) the home was updated with Queen Ann period details popular in the late 1800s. A close look at the structure reveals later additions such as the modest tower (which would have had a practical purpose, offering views of the harbor) and a decorative porch, for the summer breezes off the sea, I’ll venture — or even watching the daily parade up and down the street.

So much for the real estate pitch. Today, Joe and Mary Clabby have overseen its marvelous restoration.

Three of William’s four sons went on to become sea captains.

John William Shackford for many years commanded the steam packet ship Illinois and other ocean steamships and was then master of Jay Gould’s famous steam yacht Atalanta. (It has its own Wikipedia entry.) He died in Philadelphia in 1905.

Edward Wallace Shackford graduated from the Eastport high school, learned the trade of block and spar making at Machiasport, and then shipped on a vessel trading with the West Indies as ordinary seaman. His second voyage was on a ship that made the hazardous journey to the Pacific coast of the United States by way of Cape Horn, South America, reaching San Francisco in 1860, and sailed as far north as Puget Sound, where he passed the year 1861-62, and returned to Maine by the same route, reaching home in 1864. His next voyage was before the mast, first mate and captain of the brig Emily Fisher, commanding the brig in 1866. His next sea experience was on a steamer on the American line between Philadelphia and Liverpool, England, in the capacity of second officer, and he made four voyages on the steamships. He commanded a bark after leaving the steamship, and in 1887 resigned the command of the bark Ormus to assume a like position on the steam yacht Atalanta, owned by the aforesaid Jay Gould, on a voyage to the Mediterranean — was William introduced by his brother? He was captain of the schooner Johannah Swan, built by Albert M. Nash at his shipyards in Harrington, Maine, from 1889 up to the time the schooner was wrecked in the terrible gale of November 1898, in which gale the steamer City of Portland was lost with all on board and scarce a vestige of the vessel was ever found. William’s wrecked schooner, however, withstood the gale for seven days, when Shackford and his crew were rescued by the German bark Anna. On his arrival home, which was no longer Eastport, Shackford abandoned the life of a sailor and retired from active participation in business life.

All of this reflects the realities of sea life in a changing era.

Edward Wallace Shackford established a winter home at Harrington, Maine, and a summer home that was a “comfortable cottage by the sea,” at Point Ripley, “which has proved so delightful a summer retreat to seekers for an ideal seaside rest.”

He also found congenial spirits at the periodical meetings of Eastern Lodge, No. 7, Free and Accepted Masons, of Eastport; Dirigo Chapter, Royal Arch Masons of Cherryfield; and Tomah Tribe, No. 67, Improved Order of Red Men, of Harrington, Maine. He was elected a member and chairman of the Harrington Republican town committee. He was chairman of the Harrington school board for three years, represented his district in the house of representatives of the state of Maine in 1903-04, and was a member of the senate of the state of Maine 1905-1906. He was president of the Ripley Land Company of Maine from its organization and attended the Baptist church, where his wife was a member.

And that was essentially the end of the Shackford influence in eastern Maine.