For the first half of the 1700s, Dover Monthly Meeting was the most northern and eastern Quaker body in New England.

Friends were more or less accepted as members of the wider community, and in the 1720s they even built a second meetinghouse for those living near the village around the Lower Falls of the Cochecho – today’s downtown – in addition to the first meetinghouse serving those on Dover Neck.

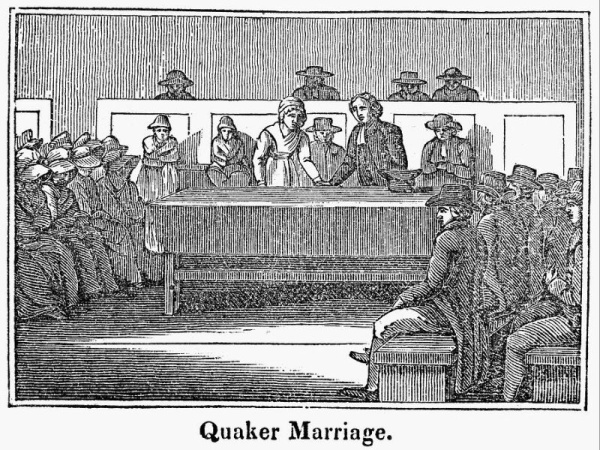

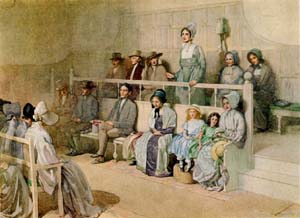

A distinctive Quaker culture had set in, one that included Plain dress and thee-and-thou language. Friends referred to First-day rather than Sunday, for example, and First Month rather than January.

There was a tightening of discipline over daily conduct and over marriages within the faith.

The Meeting and its families were also visited by traveling ministers, some of them staying for extended stretches.

~*~

Relations between the town and its taxes and other civic requirements could often be touchy. For one thing, those appointed as constables were required to serve or pay stiff fines.

In reviewing the early history of New Hampshire and Maine, I presumed that titles like Major, which we’ve seen with Richard Waldron, reflected their role in the militia. Thus, when I came across a rank applied to a Quaker surname, I figured that the individual was no longer a member of Meeting. That changed when I came across a reference to Capt. John Canney as “a Quaker who ‘affirmed'” rather than take an oath of office when he became a representative to provincial assembly, 1742-1745. Most likely, then, is that Captain was a term given to constables, the way police and fire officers today can be given ranks. Or it could also be applied to skippers of vessels.

Quakers serving as constable did face moral quandaries. On October 10, 1729, for instance, “A petition from several Quakers in behalf of themselves and their friends at Dover, praying to be exempted from gathering the Minister’s rates as Constables, was presented to the Assembly.”

The issue of collecting taxes for a minister the Friends didn’t use or respect remained.

On May 3, 1731, “The ‘people called Quakers’ again petitioned to be excused, when constables, from gathering Minister’s rates; and the Assembly excused them by enacting that such persons shall be exempted from gathering such rates of any other persuasion, and that the town should make choice of those who were not Quakers to gather the same.”

There were also tensions over expenses for the First Parish meetinghouse, which doubled as town hall.

George Wadleigh notes that March 31, 1760, appears to have been the last “public town meeting held at the old meeting house on Pine Hill,” but instead of shifting the sessions to the new building, on October 13, “At a public town meeting held at the Quaker meeting house, a committee was appointed to sell the old school house standing on Pine Hill and pay the proceeds thereof to the selectmen.”

This would have taken place at the Friends second meetinghouse, a block west of the newer First Parish home.

On January 28, 1761, “The Quakers of Dover, by Joseph Austin, Thomas Tuttle and that many persons who had agreed to do so, by the purchase of pew privileges, had neglected it, &c. a town meeting was held at which the committee for examining their accounts made report that the whole amount expended,” for the Congregational church, ” was 248pds. 18s. 4d, old tenor: which report was accepted and the building committee was empowered to sue those men who owe money towards building the house.”

That wasn’t the only issue Friends were fired up about. At that same town session, “The Quakers of Dover, by Joseph Austin, Thomas Tuttle and Samuel Austin, for and on behalf of themselves and the rest of their brethren and by order of their monthly meeting held at Cochecho the 18th day of the 10th mo. 1760, petitioned the Assembly, setting forth that they were burthened with a tax to hire soldiers into the service, and praying, for reasons assigned, to be relieved therefrom. The Assembly assigned a day for a hearing thereon, and ordered them to cause the chief officer of the Regiment, & the selectmen of the town to be served with a copy of the petition and order thereon, at their own cost and charge, that they might appear and shew cause, if any they had, why the prayer should not be granted.”

On February 6, “It was voted that the prayer thereof be granted and that the tax ordered by the Treasurer’s warrant to be assessed on the people called Quakers in the towns of Dover, Durham, Somersworth, Rochester and Barrington in the year 1760, be remitted and that the same be added to the Province Tax of said towns for the year 1761.”

On March 30, “At a public town meeting it was voted to petition the General Court for a law to empower the First Parish to transact their affairs exclusive of the other town business.”

On June 11 the next year, the church was incorporated as a parish distinct from the town government. Though this separated the two, taxes would continue to support the church and its minister perhaps as late as 1819, when the state passed its religious toleration act.

Still, on July 2, 1761, “The committee for building the new meeting house having complained that the money for that purpose had not been fully paid them, that many persons who had agreed to do so, by the purchase of pew privileges, had neglected it, &c. a town meeting was held at which the committee for examining their accounts made report … and the building committee was empowered to sue those men who owe money towards building the house.”

Though the town paid for the First Parish meetinghouse, it also used the new Quaker meetinghouse for public events. Possibly the building was larger, intended to accommodate Friends from the smaller neighboring Meetings when they came together as a Quarter.

~*~

Check out my new book, Quaking Dover, available in an iBook edition at the Apple Store.

Welcome to Dover’s upcoming 400th anniversary.