Dover, New Hampshire, sits on the tidal waters of the Atlantic Ocean but that didn’t inhibit its influence on Midwest and then West Coast Quaker growth.

Consider the leadership of Dover Friends Meeting in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Benjamin H. Jones served as clerk for six years, 1841 to 1847, and also traveled in ministry. Olney Thompson then served a year as clerk, followed by John Meader, 1848 to 1851.

In September 1852, however, “Benjamin H. Jones, having removed with his family to reside within the limits of Salem Monthly Meeting (in Iowa), inquires after a Removal Certificate thereto for himself, his wife Mahalth E. and their children, Robt H., Lucy T., and George N. Jones.” This would have been a transfer of membership taking them west of the Mississippi River.

New England’s rocky soils – usually either clay or sandy, rarely loam – had long made for difficult farming, and railroads were making Midwestern crops and livestock competitive in eastern markets.

In 1855, James Canney, an overseer and assistant clerk at Dover, moved with his family to Minneapolis and later to San Jose, California.

The Beans, who settled in Gilmanton in 1772 from Brentwood, became a remarkable case. Among their descendants was John Bean, who wed Elizabeth Hill. The four of their five children who lived to adulthood – James, Joel, and twins Mary and Elizabeth – all headed west before the Civil War. Their education included terms at the Friends Boarding School in Providence, Rhode Island – today’s Moses Brown School.

John sold the farm in Gilmanton and moved to Rochester to become a businessman. Self-inflicted financial difficulties, however, resulted in bankruptcy despite the attempts of Dover Friends John Roberts, Thomas Roberts, Elijah Jenkins, Ken Graham, Daniel Meader, and John Estes to guide him. The experience embittered and devastated him.

That may have set all four of the children looking to horizons beyond New Hampshire. They would each move to Iowa and eventually on to California and Oregon, becoming recorded ministers along the way, as did three of their four spouses, too. Quite simply, they were crucial in the establishment of Friends Meetings west of the Mississippi River.

Before going, daughter Mary wed Charles H. Tebbetts under the care of Dover Meeting on January 19, 1854. Their clearness committee was Sarah K. Prentice and Cyrus Bangs. After a stint in Iowa, the couple moved on to Pasadena. Their son, Charles E. Tebbetts, would become a prominent Quaker pastor and president of Whittier College.

James Bean went with a wagon train to Iowa and Minnesota in 1855, returned to Rochester to wed Roanna Fox on August 16, 1858, and together they moved to the prairie, where he tried his hand at a grocery and a bookstore before becoming the U.S. government paymaster and clerk for the Chippewa Indian agent. In time, they landed in San Jose.

At West Branch, Iowa, Elizabeth Bean wed Benjamin Miles, a widower with three children from Miami County, Ohio. They would move to Newberg, Oregon, where his children would establish George Fox College.

Joel Bean married Hannah Elliott Shipley in Philadelphia, but they were introduced in Iowa when she was visiting. With her prominent Quaker connections, the wedding took place in the Orange Street meetinghouse on June 29, 1859. From there, they went straight to Iowa. In the spring of 1861, they set out as Quaker missionaries to Hawaii. On their return to Iowa, he rose to the position of vice president at a bank and served as clerk of the Yearly Meeting. He and Hannah also traveled in ministry to England, 1872-1873.

So much for four humble siblings from Dover Friends Meeting. They would, however, become embroiled with controversies involving Holiness movement evangelism besetting many of the Midwestern Friends, including a shift to full-time pastors, revivals, and hymn-singing. Joel and Hannah moved on to San Jose, California, in 1882. (Their granddaughter Anna Cox Brinton, widely known among liberal 20th -century Friends, continued to use Plain speech – mostly with her husband, Howard.) They were joined by James and Roanna.

Dover’s former clerk, Benjamin H. Jones, had returned east, to Lynn, Massachusetts, but was about to try homesteading in Montana with his wife. His son, George, was already in San Jose.

In the end, rather than join California Yearly Meeting, the San Jose Meeting remained independent. Officially, after being disowned by Iowa Friends after he had left, Joel and Hannah applied for membership in Dover Meeting, despite the distance, and were welcomed.

As far as pioneering went, they were way ahead of the high-tech revolution that would take place in their final locale.

~*~

Add to that Tom Hamm’s book, The Transformation of American Quakerism: Orthodox Friends, 1800-1907, which details the impact of railroads and commercial farming on Friends’ life during the nineteenth century, especially across the fertile Midwest.

During this time, the wider Quaker world underwent a number of modifications. Gone in some circles was the restrictive discipline, along with the requirements of Plain speech and dress and the marriage limitations, but sometimes it came with theological strife and new legalism.

By the end of the century, pastors had been introduced through much of the American Quaker world, including Gonic and Meaderboro. Friends had influential roles in interfaith organizations such as the YMCA, too.

~*~

In 1884, Asa C. and Emeline Howard Tuttle, along with their son, returned to Dover “after spending some years among the Modoc Indians in Indian Territory,” as James Bean observed. “They were both ministers of ability. They remained in Dover, beloved and respected by all until Asa’s death in 1898, when Emeline removed to Rhode Island. and later to Louisiana. After the removal of Emeline Tuttle and Lydia E. Jenkins, the meeting continued without a regular minister for some years.”

Emeline is credited with discontinuing the separate men’s and women’s business meetings in 1886 and merging them into one.

~*~

In 1913, the faithful remnant proved to be too small and too old to continue on its own and regular worship was discontinued in the meetinghouse. Officially, Dover Monthly Meeting went on at the Gonic meetinghouse, which had both a pastor and financial support from the mill there.

~*~

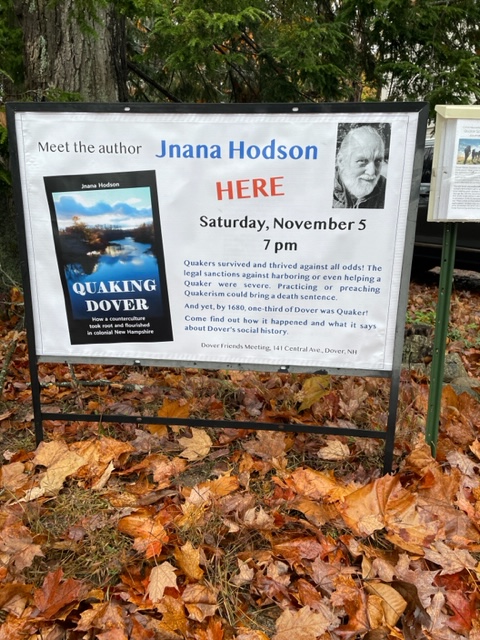

Check out my new book, Quaking Dover, available in an iBook edition at the Apple Store.

Welcome to Dover’s upcoming 400th anniversary.