We can wonder how much of the history I could have captured if I had owned a camera. The images I’m digging up for this series help some, but skirt much of the grittier realities I faced.

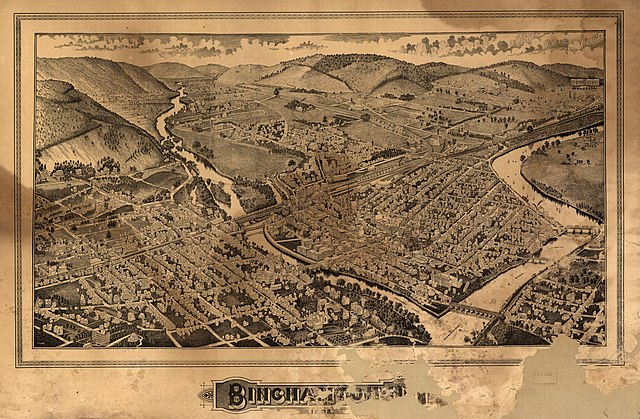

The city itself was already well into Rust Belt decline and probably would have been intolerable apart from the hippie-era adventure of living in a college-town slum.

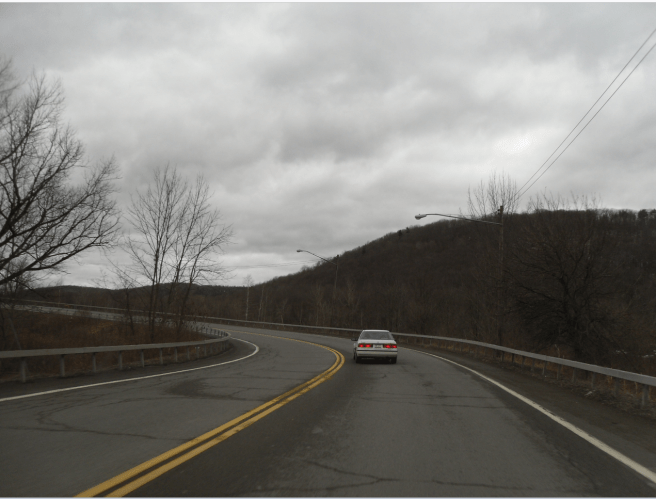

This was my introduction to the East Coast, and my first time of living in proximity to mountains, albeit the Allegany foothills of the Apalachin range (New York spellings). I was still spellbound. The region was called the Southern Tier, to the west of the Catskills and south of the Finger Lakes. The city,- or Tri-Cities when neighboring Johnson City and Endicott were included, was generally working-class and infused with a spectrum of ethnic minorities.

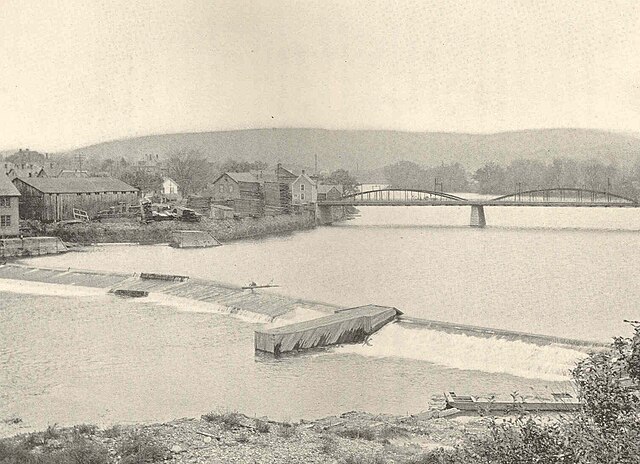

The city was nestled into the valley and once had water-powered mills along the riverbanks.

The Susquehanna itself was a fascinating river, as I present in my chapbook of poems carrying its name.