Continuing the history of our old house:

Gordon and Calla Greenlaw purchased the house in January 1975 but then sold in in December of that year to Frank and Georgia Miliano.

With the Greenlaws, the plot takes a distinct turn. Gordon received a Purple Heart award in World War II. He died in August 2014 in Florida and was buried at the Maine Veterans Memorial Cemetery in Augusta.

Crucially, this was a second marriage for both of them, sometime before mid-1969.

Greenlaw and its variant, Greenlow, is another surname that goes back in Downeast history, as I’m finding.

He engaged in a string of real estate transactions — 66 in Washington County, from what I found in a quick survey, some of them purchases of properties seized on tax liens.

She predeceased him by a month, and while her obituary dutifully named her as Mrs. Calla R. Greenlaw, she was buried alongside her Magoon kin in her native Crawford, a distance from Augusta. It was noted that she died peacefully in her sleep of natural causes but curiously no location was mentioned. She was 99.

As the obituary observed, “Mrs. Greenlaw lived the greater part of her life in Eastport. She attended school in Crawford and Calais. She was the consummate businesswoman. She worked in the Calais Post Office for many years and later owned and operated the Red Ranch Inn in Eastport and dabbled in real estate.”

Mention of the Red Ranch Inn raises some eyebrows. It still has a reputation as a roughneck bar in its time, the kind where everybody would roll out onto the State Route 190 (the only road into town) for a wild brawl. The kind where the Washington County sheriff would show up with a Thompson submachine gun and fire off a clip in the air to get their attention. Yet, also, the kind where a seasoned waitress could walk between the combatants to calm them down. For others, its appeal was music and dancing, “a lot of fun,” as more than one woman has told me. Usually, the music was from a well-stocked jukebox, though there was the occasional live band. As for the fights? “It did have some action,” as one replied tersely with a sly grin. Do note that “consummate businesswoman” Callie alone is named in the obituary as the owner and operator.

There’s a good reason why. Her first husband, Milton A. Peacock, in partnership with Robert L. Tait, bought the restaurant in June 1963 from its founder, William J. “Bill” Bowen senior. In November 1965, while living in Los Angeles, Tait sold his half-interest to Peacock. That month, Milton and his wife, Calla R. Peacock, sold the restaurant by a warranty deed to Gordon Greenlaw. Yes, her future husband. In a 1967 real estate sale, Gordon was listed as a single man (more accurately, divorced) and that transaction was witnessed by Calla Peacock. By July 1969, though, she was Calla R. Greenlaw in the property dealings.

Did Gordon have any role in running the restaurant or its bar? The picture gets complicated, thanks to the presence of D & V Inc. of Bangor, which somehow concurrently owned the property or the business or both. While Bill was recognized as the restaurant founder, D & V applied for the liquor license in 1969.

A black-and-white photo of the Red Ranch presents an isolated building across the railroad tracks, a kind of diner with huge letters PIZZA emblazoned along the exterior and a two-story farmhouse attached to one side. Another photo found online has the interior with the jukebox and a row of counter stools that were always full, as a comment noted, along with the fact that they were beige, not red.

As for the food? Several women have said, “I couldn’t go there till I was old enough to drink.” Another, though, insists the menu was good.

The Greenlaws apparently exited the scene when D & V sold the Red Ranch to Ernest J. “Ernie” Guay in 1972 — three years before the Greenlaws bought our house. Under Ernie, the restaurant became a bar only. Sometime after that, Jeanette, his wife, used it for an antique shop. In the end, it served as a bottle- and can-deposit redemption center.

The structure was erased from the landscape when their son, Ernest junior, sold it in 2003 and Cornerstone Baptist Church was erected the next year. So much for an overlooked footnote of local history.

Calla’s real estate business involved owning rental properties around town, or so I’m told.

One claim in the obituary especially intrigues us. “Calla missed her calling as a master carpenter. In her heyday she could build anything and was meticulous to a fault. Anything she put together had to be exact, and all work would stop until it met her specifications.”

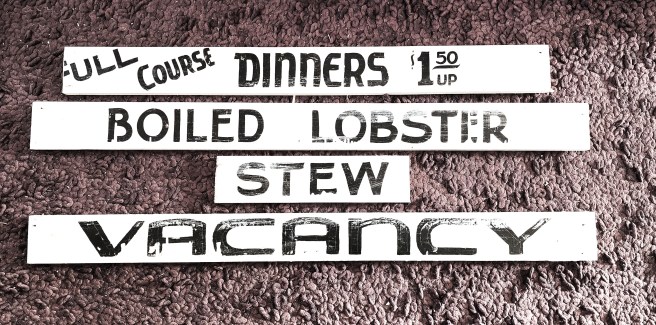

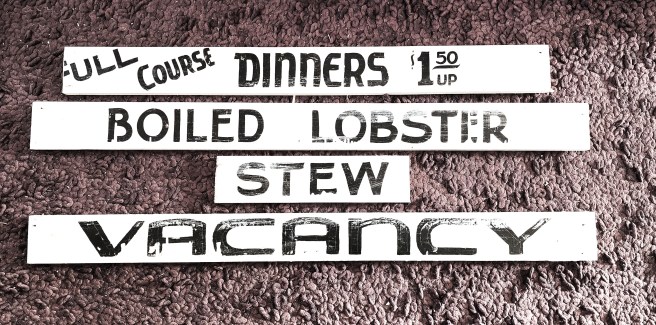

At first, we didn’t see much evidence of that in our house, but it soon prompted speculation of which ‘70s touches were hers. In our renovations upstairs, the back side of baseboards we removed had the professionally lettered words STEW, and then VACANCY, BOILED LOBSTER, and, my favorite, FULL COURSE DINNERS $1.50 UP. We’re keeping those, though we’re not yet sure where.

I originally thought they were from the Red Ranch, a reflection of the Yankee frugality that recycles forever, if it can. Do note that no paint was squandered covering the lettering, since it was facing the wall anyway. Or was it intended for future history, the way a time capsule is?

Well, the obituary did insist, “She loved working and was always busy.” Did that include cooking or even gardening? The kitchen wasn’t a master chef’s ideal. Leave it at that.

The obituary also acknowledged, “She raised and adored her poodles. She always had at least two of them running around.” That might account for some of the badly scratched doors and floors. Poodles, I’ve heard, attract a specific fandom, usually not of the Wild West saloon crowd. That would have suggested pit bulls or, dare we venture, mastiffs.

Regardless, “In her later years she wintered in Florida but always called Eastport her home.”

One thing the obituary didn’t mention was an earlier marriage to Milton Peacock, the father of her daughter Sandra R. Stevens. After the divorce, he relocated to South Portland and Sanford, Maine, and is likely buried in Brunswick, Maine, amid Mitchells — perhaps his sister and brother-in-law?

Curiously, Calla and Sandra share a twin-hearts, mother-daughter headstone in Crawford reflecting what I’ll assume was a close emotional bond. The daughter died in Bangor a year before her mother, and, from what I find, had married at 18. That marriage ended in divorce. The second is more nebulous, though he died in 1993 in Newfoundland and Labrador and is buried in Eastport. I still have no clue to how her Stevens surname fits in. Not that it matters in terms of our old house.

Also buried in Crawford is Calla’s grandfather who inspired a 1988 book, George Magoon and the Downeast Game War. He adamantly resisted Maine’s early 1900s’ hunting laws, especially the part about having to buy a license.

That said, what interests me is a sense of a lifestyle for our occupants over the years, along with the many remaining questions. For our Greenlaws, especially, dare we call it colorful?

From what I see in Gordon’s real estate transfers, the Greenlaws didn’t live in the house much, if at all. Their address was soon the house just to the north, as well as properties at the other end of Water Street.