In following the history of our house, we’ve veered off from Captain John and Esther’s children as other families added their names to the dwelling. At this point, I’d like to return to the Shackfords to give you a better sense of the family’s additional impact on the community as well as ways the town itself changed over the years. When the Shackfords first arrived, the place wasn’t even called Eastport but rather Passamaquoddy or Moose Island on Passamaquoddy Bay. Sometimes it even went by all three at once. While the sons’ and sons-in-law’s escapades during the War of 1812 have been noted, their seafaring ventures continued well after.

~*~

John junior, for instance, not only commanded the first vessel owned in the town, but he also ran the first packet in the Boston and Eastport line, “through winter’s storms and summer’s fogs.” A packet was a new concept in shipping, with vessels departing on a regular schedule, rather than waiting for a full load or a set number of passengers. The innovation could be risky for the investors or highly profitable, depending.

In a fuller telling, he “was commander of the first vessel owned in the town and commander on the first freight and passenger traffic boat established between Eastport, Portland, and Boston, and his last packet, the Boundary, the swiftest vessel on the coast after 21 years in this service, had to give place to steamships.”

The May 9, 1828, edition of the Eastern Argus announced that the schooner Boundary, 142 tons with John Shackford, master, the schooner Edward Preble, and the Thomas Rogers would be running between Eastport and Boston, stopping at Portland both directions. That gives us a date and a possible commercial association of the three vessels. After that, newspaper mentions of the Boundary arriving or departing Eastport or Boston with Captain Shackford at the helm were common.

He “knew by sight all the dangerous places along the coast, but never had more than a passing acquaintance with them, and during his long experience as shipmaster never had occasion to call upon his underwriters for a dollar. The Boundary, his last packet, so well known as the swiftest vessel on the coast, was driven off the route on the introduction of steamships, when she was 21 years old; but for 20 years after she was a staunch craft, engaged in the coasting trade.”

Coasting, should you wonder, refers to traffic that followed the coastline rather than crossing the open ocean. The swift, agile coasting schooners could easily run into trouble further out from the coast.

The December 2011 edition of the Maine Coastal News described the Boundary as having two masts and dimensions 79 by 22 by 9 feet. And, yes, she was built on Shackford Cove in 1825 by Robert Huston.

There was a legal tangle on June 26, 1826, when, as commander of the Boundary, Captain John appeared before the Boston board of alderman to respond to charges of an alleged breach of the law to prevent the introduction of paupers from foreign ports.

Captain John junior’s sons included three shipmasters: Benjamin Batson Shackford, who died in Eastport in 1885, aged 73; Charles William Shackford, master of the brig Esther Elizabeth, who with his vessel was lost at sea in the winter of 1853-1854; and John Lincoln Shackford., who died at St. Thomas, West Indies. More on him later.

John’s wife, Elizabeth Batson, came from another seafaring family. She died in 1830. Did she travel with him, as many captains’ wives and families did? I suspect he married a second time, perhaps to Eliza A. who died in Eastport on February 17, 1899, age 84 years four months five days.

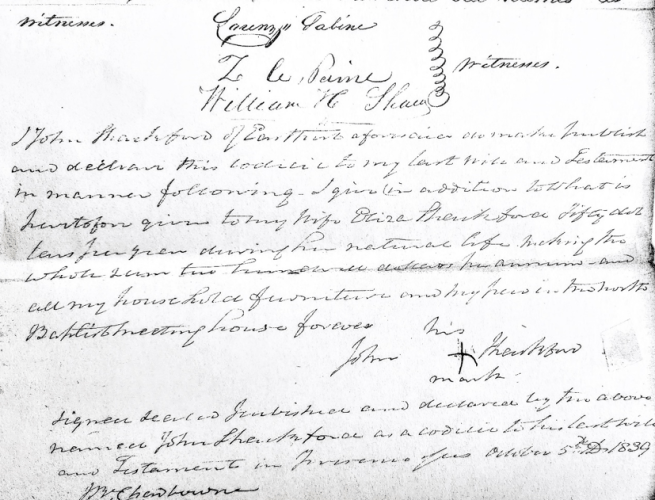

When John junior died on August 12, 1866, he left no will. His obituary in the Eastport Sentinel, in the manner of the time, did not name other family members, something that might have revealed whether he had remarried after his first wife’s decease. Instead, it said, “He was a devotional man always found at prayer meetings and public preaching when he was able to be there.”

Remember, John junior grew up in the house we now own.