Born in 1837 on Campobello Island, New Brunswick, to Ames and Amy (Creighton) Buck, Fisher and his family were living in Maine by 1843.

In the 1850 Eastport Census, Ames was a blacksmith, 49, born in New Brunswick. His wife was 50; and the children were clerk George, 22; Mary E., 19; Amy, 18; blacksmith Joshua, 17; Abigail, 15; [Fisher] Ames, 13; Anna M., 11; [Adelaide] Sophia A., 10, all born in New Brunswick; and John F., 7, born in Maine.

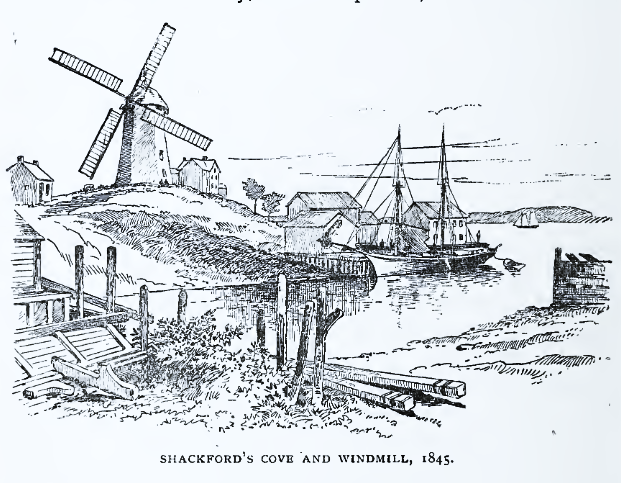

In 1855 Ames owned a house diagonally across Water Street from ours. An alley ran beside their house from Water to Sea Street, providing ready access to the Shackford wharves, as well as one labeled Buck and the A. Buck and Company steam mill attached to the William Newcomb sash and blind factory.

Ames was one of the six sons of Jacob Buck, half-brother of the Bucksport founder. Another son was Eliphalet, who landed in Eastport and is buried in neighboring Robbinston.

In the 1870 U.S. Census, his family included school teachers Mary, 29; and Ada, 25, and fish dealer John, 21. The wharf makes sense. And son Fisher Ames Buck had a household of his own.

The 1879 map shows a J.S. Buck wharf as No. 32 just below the Water Street property, presumably John S. Buck, and nothing for the Shackfords, who had previously owned multiple wharves there.

By the time of his death, Ames was described as both a blacksmith and a machinist.

Incidentally, Ames’ headstone in Hillside Cemetery gives 1796 for his birth and erroneously names daughter Amy Cory (1880-1886) as his wife. The date of his death is a year earlier than some other accounts I’ve seen.

~*~

In turn, Fisher married Clarissa Alice Bailey (1842-1922) in 1865. Their children include twins Frances F. Buck (1872-1934) and Frank Clifford Buck (1872-1950), William Edwin Buck (1875-1935), Alice M. (circa 1879-1955), and two who died in childhood, Harry C. and Jesse B.

Like his father, he was a blacksmith. Later he was an engineer. He was also a freemason, as was son William Edwin, and he served as a town selectman, 1874-1879.

He was among the subscribers underwriting Kilby’s 1888 history, along with a George N. Buck of San Francisco (his brother?).

Fisher died April 5, 1910, of pneumonia. He is buried at Hillside Cemetery in Eastport.

~*~

His son William Edwin Buck was father to Clifford Hilyard Buck (1899-1973). I do wonder whether they lived in the house or whether other family members did or whether it was rented out or even largely vacant during the period.

~*~

The Tides Institute & Museum of Art’s online photo collection of Eastport houses calls ours the Commander Albert Buck house, with the note: “He returned (after World War II) to Eastport with Rose and settled in the family house at the corner of Third and Water Streets.”

Commander Albert Clifford Buck (1886-1951), a U.S. Navy veteran of World War I and World War II, is buried at Hillside. He was 64. The headstone also names Elizabeth E. Lizzie Sears Buck (1851-1907). Who is she, other than born in Woodland, Washington County? Not Rose, obviously.

Albert, it turns out, was born to Fisher’s brother, John, the fish dealer.

So how did he wind up with the house? Forty years passed between Fisher’s death and Albert’s, and family members may have moved elsewhere for employment and other reasons. Perhaps the others simply weren’t interested. Who, in fact, inhabited the house in the interlude?

The neighborhood did have a number of Lebanese families by the early 1900s, attracted to jobs in the sardine canneries that ruled the local economy after the wooden shipbuilding industry collapsed.

Albert’s obituary mentioned that he had maintained a summer home in Eastport since the end of World War II, but neglected to note where his fulltime residence was. It also named a son, Charles S., stationed in Arizona (in 1951,) and brothers Milford in Rowley, Massachusetts, and George of New York City. (Milford R. Buck (-1952) is buried at Hillside. George is another mystery. The obituary also said the funeral service would be at the Washington Street Baptist church and that Albert was a freemason.

Just two years later, Charles, age 40, died of meningitis at the Veterans Administration Hospital in Tucson, Arizona. He was an automotive mechanic and, according to the state certificate of death, was born March 13, 1913, in Massachusetts, to Albert C. Buck, born Maine, and Rose A. Mayer, born Massachusetts. In addition, he was buried in Rowley. What was the family connection there?

I’m guessing it’s where Rose’s family was. Albert was likely at sea for extended periods. In short, he wasn’t in Eastport.

Our home, by the way, had an unobstructed view of the water.